Review written by guest writer John Pietaro:

Within the pantheon of new music that was birthed through jazz in particular, the political content has been brazenly, pridefully Left. Sounds of protest easily predate the artform as we know it, indeed slave poetry, field hollers, and the roots of the blues were foremost the folk art of liberation, but as jazz came to be, the struggle for expression itself was profound to a population enchained. To those paying attention, the question of why a certain artist within this music is “so political” is itself a misnomer. By nature, jazz, especially in its more radical form, is a political statement. Taking this concept into the post-modern, works both through-composed and freely improvised, orchestrated or formed by conduction, and with the addition of international cultures and revolutionary poetry, the struggle of a people becomes the struggle of a cause. Social justice in many hues, many voices.

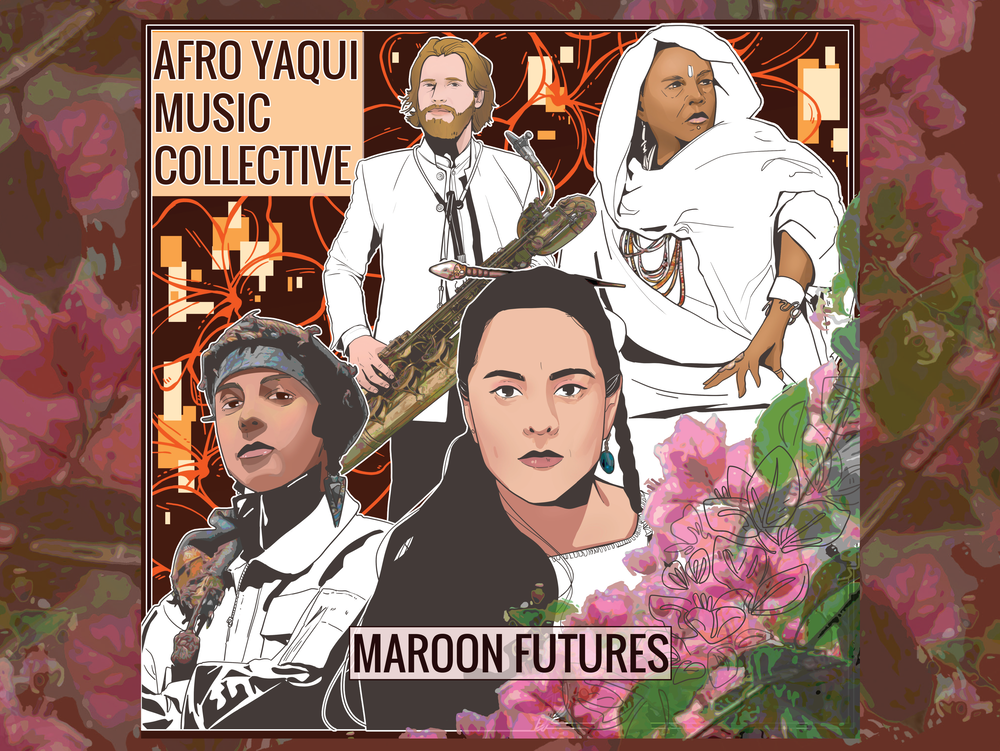

The Afro Yaqui Music Collective, the self-described “post-colonial big band”, is the embodiment of this expanded struggle even while thriving on the aesthetics of an advanced music. Guided by Ben Barson, a protege of the late Fred Ho, this 15-piece ensemble wears its multi-cultural, multi-lingual coat of arms with pride and intent. The band’s socio-politics shines as much as its inherent swing, groove and the captivating orchestrations of its leader. Maroon Futures, the Collective’s sophomore release, is dedicated to the cause of Russell Maroon Shoatz, political prisoner of the Pennsylvania system for some fifty years, thirty of which he bore within solitary confinement. Barson was at the heart of one of Ho’s final works, a suite which raised funds and awareness for the cause of Shoatz. That work was directed in performance by another radical stalwart, Salim Washington, due to the state of Ho’s illness at the time, still, Barson has advanced the cause to a new level. The Afro Yaqui Music Collective seems to have picked up where Charlie Haden’s grand Liberation Music Orchestra left off, though comprised of lesser-known artists. No small feat.

The album’s liner notes speak of the effects of 2020’s pandemic as well as its uprisings: the people’s fight against (as Shoatz dubbed it) “patriarchal capitalism” as realized in racist policing, rampant sexism, and the commodification of natural resources. Most profound is the call for a revolutionary matriarchy to effect necessary change. Appropriately, the album opens with “Nonantzin”, for Mother Earth, which marries jazz-funk to the ancient language of Nahuatl, itself an example of a pre-Columbian, maternalistic society. Composed by Salvador Moreno, the melody is carried by the flowing vocal by Gizelxanath Rodriguez, a principal of the Collective whose own origin is Mexican. Barson’s low horn covets the bottom as handily as Rodriguez’s voice soars above the supple arrangement. The multiculturalism expands further with the use of stop-time to herald in solo statements, particularly when drummer Julian Powell’s backbeat, in the absence of other instruments, recalls that very traditional and stark blues stomp. But this cut is where the one-world sound only begins. “Sister Soul”’s Chinese pipa lead (by Yang Jin) is initially retained beneath the gorgeous vocal by Charlotte O’Neal, and then onto the hip hop spoken word of Nejma Nefertiti and O’Neal. The call for that revolutionary matriarchy couldn’t be clearer, but bassist Beni Rossman’s sinewy R&B chops are also standout here.

The global unity takes flight on “La Cigarra” by composer Raymundo Perez y Soto, a roving work which floats between 6/8 and 7/8 meters, calling on memories of apropos Spanish Civil War songs and the vast Middle Eastern musical tradition. Daro Behroozi’s moving solos on both tenor saxophone and ney flute walk between these worlds, traditions old and of-the-moment, as the lyric symbolizes the underground existence of political prisoners.

However, the central work of Maroon Futures is one by Fred Ho, brought to new life under the hand of Barson and company. “We Refuse to Be Used and Abused,” also known as “Unity” (for the Struggle of Workers”), the strength of this message is as apparent in the Collective’s realization as in Ho’s revolutionary intent. Listen for the story as told within solo statements by electric guitarist John Bagnato, alto saxophonist Alec Zander Redd, and Barson. But the work rolls out with deliberation and utmost urgency through an alluringly Ellingtonian saxophone section theme. It seems too easy to state that the band is on fire here, but this critic can find no better description. The thematic material shimmers in that 1930s Harlem manner but then turns heavy on the pocket groove as Nefertiti’s empowering rap lyric is accompanied by the band’s shouts. Classic big band swing with hip hop interplay in the post-colonial global village. Listen once to eat up the vital statements, but then listen again to focus on the solos, particularly that of Bagnato who simply shreds the atmosphere. The Afro Yaqui Music Collective is not your father’s (or grandfather’s) big band; it is the one we’ve been waiting for. But if they should take on the Savoy Ballroom, the resonance will be historic.