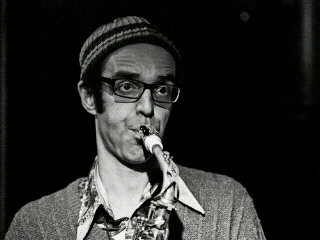

This month, New York is being treated to six exciting performances by master alto saxophonist Michael Attias. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see all that this artist has to offer. The centerpiece of the month is a four-night residency at Ibeam, book-ended by two performances at other venues. These are all must-see performances. See below the program for an interview with Attias about his upcoming performances, his background as an artist, and his thoughts on aesthetics, among other things.

July Program for Michael Attias

Muchmore’s (Williamsburg, Brooklyn)

July 14: Think Shadow (Sean Conly & Michael Attias) at the OutNow Festival

Ibeam Residency (Gowanus, Brooklyn)

July 16: Trees: Michael Attias, John Hebert, Ralph Alessi; preceded by solo sets from each, 8, 9:30 pm

July 17: Anthony Coleman Trio with Mike Pride, Michael Attias; Ben Gerstein solo; Music without Autumn Sonata: Attias, Gerstein, Anthony Coleman, Mike Pride, 8:30, 9:30, 10 pm

July 18: Michael Attias-Sean Conly-Tom Rainey; Michael Attias’ Spun Tree: Michael Attias, Ralph Alessi, Matt Mitchell, Sean Conly, Tom Rainey, 8:30, 10 pm

July 19: Michael Attias-Matt Mitchell Duo; Michael Attias’ Spun Tree: Michael Attias, Ralph Alessi, Matt Mitchell, Sean Conly, Tom Rainey, 8, 9 pm

Korzo (Park Slope, Brooklyn)

July 28: Michael Attias Quartet with Aruan Ortiz, John Hebert, Nasheet Waits

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Interview

Cisco Bradley: What are you planning for your residency?

Michael Attias: Well, actually a couple of nights before the residency is the Think Shadow gig on July 14th. This is part of the OutNow Mini-Fest at Muchmore’s in Wiliamsburg. OutNow is the label that put out our album.

Sean and I are going to play duo. Sean’s just one of my brothers and heroes. He’s been the guiding force behind this project, The music is generally free improvised with the idea that we’re really playing songs. We’re listening and we’re dealing with the material harmonically as if we were playing a song that we already knew but we’re actually making it up. So, in that sense it’s I think Ornette [Coleman], Paul Bley, [Paul] Motian, all of those kind of influences and references are there. But, Sean has also been really getting into the textural aspects of playing the bass and extended techniques in a solo context. And, that language somehow really works in this duo context. The name Think Shadow comes from a in line in a poem by Louis Zukofsky, “See sun, think shadow”.

So, the first night of my residency at Ibeam July 16th: John Hebert, Ralph Alessi and I are going to start it with three short solo sets. I’ll start the residency playing solo. Saxophone and piano. Hebert will do a solo set that’s dedicated to LeBron James. I’m not sure what Ralph is going to do. It’s going to be the first encounter of just the three of us. I think we’ll play some songs and improvise a lot. I’m really excited about it.

Cisco Bradley: Can you tell us any more about what you’re planning for the three of you?

Michael Attias: John mentioned that he wanted to play some of the material we played with Ralph on the last RENKU gig which was at Cornelia Street [Café]. It was Satoshi, John, and me, plus Ralph Alessi and Chris Hoffman as guests. So, I think we’re gonna play some of that music. In a way, it’s a RENKU gig with Ralph subbing for Satoshi.

Ralph has that kind of ability to get out of the way of the material, of letting it evolve with a kind of incredible naturalness. Ralph shapes time. He shapes the sound but he also shapes the negative space between the sounds. He makes me hear both sides of it. I see light, I hear light between the notes. And, he’s implying all these different worlds with each phrase as if he’s riding across different currents of the rhythm, of the harmony, of the melody and implying them with this incredible concision. Such a great improviser. Also, that sense of playing within an ensemble and shifting roles, being able to play in different levels, different strata in the music. And, just a great melodic ear and a sense of humor. With all the amazing kind of technique and grounding that he has in classical music and so on, he has this gift of being able to access his beginner sound. The sound of this kind of pure overtone of the trumpet. There’s an intro on the Spun Tree album that he plays solo. It’s just beautiful. I don’t know what instrument that is. It’s gorgeous. Just a great spontaneous wizard. So, I’m excited and a little afraid. I think I’m probably going to be laying out a lot and just listening to them.

Cisco Bradley: Anthony Coleman Trio. So, is this a group that you have played in for a long time?

Michael Attias: No. This group has played over the last maybe year or two years. It’s played three or four times. The first time we played was when Anthony had a residency at The Stone. Was that the first time? It was a great gig.

Cisco Bradley: Last year?

Michael Attias: Yeah. I don’t know if that was the first time or if we’d already done it with Mike [Pride] or not. But, I’ve played with Anthony for many years. He’s one of the people I’ve played with more than anyone. We’ve made a few records together. He just has a new album that’s coming out — that came out last week – on New World which features his chamber music.

I wrote the liner notes actually. So, to know how I feel about Anthony and my understanding of his music, then read the liner notes to the New World album. I think they’re actually on the website. It’s a great record. I’m really, really proud to be on it.

I don’t know what Anthony is thinking for that set exactly. I know some of the sources for the music that we play, which is all improvised, I know that some of the references would be the common love we have for the Pygmy Ocora recordings. This mesh of rhythmic, hocketing textures. We’re all into that.

Mike always brings these kind of incredible instruments in his drums, these big snares or these wild bass drums. He knows that Anthony really, really loves — early jazz drummers like Baby Dodds and Zutty Singleton, the pre-ride cymbal way that they play time, the shifting orchestrations, and the time feel. So, that’s kind of in there along with Cecil Taylor trio: Jimmy Lyons, Andrew Cyrille, and Cecil Taylor.

Not that we want to sound like them but I know that that’s in there somewhere, a textural mesh. Something in common between Pygmy music, early Hot Five or King Oliver and the Cecil Taylor Trio. It’s somewhere living in those zones.

And, then Ben Gerstein is going play a solo set. Ben is a great friend, also, an inspiration, not just for me, for a lot of people – in his work ethic, in his imagination, and his sense of humor. He seems to have given himself the project of translating the entire world of music into the trombone over the past few years. You can go to his website. It’s kind of mind-blowing. The most recent one, that I know of, is the Stravinsky Movements for Piano and Orchestra, which is this series of five miniatures that he’s redone entirely with trombone. He plays all the orchestra parts with different kinds of mutes. I think he’s using six different kinds of mutes, maybe eight. And, then the piano is open horn. It’s amazing. There’s something about it that’s kind of like a monk in a monastery. Really sound by sound, overdubbing trombone and then creating this world. It also reveals something essential about the music. And he’s done that with Bach, with Vivaldi, with Elliott Carter, with recordings of Yiddish storytelling, getting exactly the inflections of the voice. You know, all of it trombone. It’s kind of insane and brilliant and great.

I love improvising with Ben and I love what he does with what he’s working on. He’s really doing it kind of in the margins of the official world of music making. And, he’s getting to be pretty revered and extremely respected by all kinds of musicians and people for that and for sticking to that – to his vision, to his path.

Cisco Bradley: Do you know what he may be planning for that session?

Michael Attias: Whatever he wants. I’m excited. I don’t know. He has so many different things that he’s into. There’s one thing in particular, which I hope he’ll do but I don’t know, where he’s using recordings that he puts inside the bell of the trombone.

Cisco Bradley: Yes, I’ve seen this.

Michael Attias: You’ve seen Ben do that? I mean, it’s kind of so simple and so brilliant. And, then he’s gonna be joining Anthony, Mike, and I in something that I’m kind of obscurely calling Music without Autumn Sonata. Autumn Sonata was a Bergman film that was adapted for theater and I did music for at Yale Repertory Theater.

I should say in this kind of big overview, that one of the biggest influences and influential persons in my life and encounters has been the theatre director Robert Woodruff. Working with him changed my way of conceiving time and the possibilities of performance. I have done sound and music for five shows, I think, with him at this point, most of them live. One of them I did with Satoshi. The two of us, we lived in New Haven for weeks rehearsing every day and then doing eight shows a week at Yale Rep.

Robert gives me a lot of space to experiment with how the sound and the musical gestures live inside of a theatrical space: live with the text, live with the lights, the clothes, the set, the gestures, which you then conceive of as a whole. This is something very few directors are really open to doing. A lot of them talk about collaboration but I have never encountered a spirit of collaboration like his, which is also one of challenge. It’s tough stuff and it’s great. So, one of the shows that I composed music for was Autumn Sonata, his remake or adaptation or remix of the Bergman film. The main part of the score was a solo piano piece that I wrote for one of the characters. The paralyzed, mute daughter, she has no text but she’s in the film and she was in the production, and she was played by the wonderful actress/pianist Merritt Janson So, she doesn’t speak, but she plays piano behind a screen which lifts midway through the show and you see that the music you’ve been hearing is been played live by Helena, the disabled daughter of a concert pianist. So, I really wrote it for her character. It’s the inner life of her character, this piano music. And, I wrote it on Anthony’s piano. I stayed at his place while he was on tour. I needed a piano to write on. So, this is going be the first time that it’s played since that production which happened in 2011. I’m excited.

Cisco Bradley: That’s the end of night two of the residency.

Michael Attias: Yeah. And, then the next two nights will be around the band Spun Tree. It’ll be mostly new music and some from our record.

Cisco Bradley: So, you with Sean Conly and Rainey and then the full band?

Michael Attias: Yeah. The first night, we’re going play trio. Improvise as trio and, then we’ll play a quintet set. And, then the next night, Matt and I will play a duo set and then we’ll play another quintet set. And, that will be the end of the residency. The 19th will also be Matt’s birthday.

Cisco Bradley: Cool. Are you working towards another record with that band?

Michael Attias: I hope so. I’m trying to get funding to do it or a label or whatever. The music is pretty close to ready. I think after these two gigs it will be. So, I hope at some point there is a way to make that happen. There’s enough for two new records. Labels, wake up!

Cisco Bradley: And, then you have two other things after? Your quartet’s playing at…

Michael Attias: So, the new quartet is with John Hébert, Aruan Ortiz, and Nasheet Waits. Aruan is a piano player. I think he has a new album coming up with Eric Revis and Gerald Cleaver. A trio. He’s really, really wonderful. It was a great encounter to meet him and start playing with him. We’ve played one duo concert and then a few of these quartet gigs and, we did one gig of his music with Jonathan Finlayson and Nasheet Waits as a quartet at Cornelia Street last year. That was really a blast. I hope we can do more of that. He has a great sound and is open to a lot of visionary speculation. Thinking about architecture and thinking about nature.

What I really love in him is he has this kind of love of math, you know, conceptual mathematical speculation but, he brings the body to it, the sound to it. It’s extremely physical and rhythmic. But, he’s reaching. He’s one of those players that really reaches. All of these players. They’re all like really characterized by that. They’ve taken enormous risks, including with their own image or whatever you would expect them to do.

None of them are the kind of player who’s just going to kind of rest on whatever you expect of them, on what their strengths are. Every time they play, they reach. They reach for something that they can’t do or that they can barely pull off. I’m always much more interested in that than in somebody showing everything they can already do.

I feel like when I see that, the display of a mastery that’s not reaching, that’s content with itself, I feel like it doesn’t need me as a listener. It doesn’t need me to be there. As a listener I want something where the players are confronted with some kind of unknown. It then gives me as a listener room to experience it. I’m in there. I believe in a democracy of ears. I really feel the importance of the audience in that sense that when you’re playing – we’re really all of us confronted with the unknown at that moment and trying to make sense of this information that’s happening – all these sounds and these intentions – I’m just barely one step ahead of the audience, or they’re ahead of me, it’s a dance and it’s that shared openness to the unknown which connects us, connects our experiences of the moment. I mean if you are engaged at all as an active listener to music, whether you’re doing it consciously or just doing it naturally, your mind, your ears, your body is trying to process all of this stuff. I think they really feel it. It moves them and it brings them in, whether they’ve heard that kind of music before or not.

Records are much harder because you have to kind of re-create the bodies. You have to visualize the fact that people are making these decisions. In a way you have to have had experience before to know what these sounds that you’re getting through your sound system are referring to. Like what the physical human reference is. But, when it’s live, I think audiences should be given the credit of being able to engage with that rather than being spoon-fed some stuff that everybody knows already. I think that’s where the industry complex gets it completely wrong.

We were talking about the Knitting Factory, I remember being in the Tap Bar, one night during some festival, it was packed and there were rock bands playing upstairs. So, there were all of kinds of audiences mixing. And it was a beautiful concert with with [Mark] Dresser, Ray Anderson, Gerry Hemingway, Michael Moore playing really challenging, advanced abstract music. And, you could have heard a pin drop because the players were so engaged, they were so listening, they were so on the edge and not taking anything for granted. And the audience, many of whom had probably never heard anything like it, was completely wondering what is gonna happen? People felt it. It was real and it was honest. So, anyway, Aruan is like that, Nasheet is like that. I’m excited about the quartet. If I could make a new record right now, it would be that group. It would be that band.

Cisco Bradley: I would like to also have you talk about your background. How did you first come to New York and what had you been doing musically prior to arriving here?

Michael Attias: I came to New York 21 years ago, in January of ‘94.

Cisco Bradley: Where were you coming from?

Michael Attias: About 10 years of back and forth between the US and France. Immediately prior to that was Paris for a few months, less than a year. I’d been in Middletown before that. I spent a semester at Wesleyan University kind of just to be there with Braxton at the time. That was incredible.

Actually, the first rent that I paid in New York came from a duo gig that I did with Braxton at a festival on the Belgian/French Border, which was a wonderful surprise. I got a call from his agent to go do that just as I was trying to figure out how am I gonna pay, how am I gonna survive here. So, it was sweet.

I was remembering that occasion recently because driving back to Paris to the airport, the festival people were driving us back to the airport and picking up Ornette [Coleman] because he was playing the next night on the same festival, and so I saw them meet. And, they hadn’t seen each other in many years. I think Anthony used to live at Ornette’s in that loft at on Prince Street when Braxton came back from France. I think there was a period where he kind of stopped playing music and was just playing chess in Washington Square and living with Ornette.

There’s a book called As Serious As Your Life, the Valerie Wilmer book. Great book, covering the music from the time. She was a British photographer who knew a lot of the musicians. There’s a picture of Ornette and Braxton and Dewey [Redman] and Leroy Jenkins shooting pool. Anyway, they hadn’t seen each other in a long time.

Ornette was my greatest hero inspiration. I first met him when I was 15 backstage after a concert.

Cisco Bradley: In New York?

Michael Attias: No. that was in Minneapolis. I met him three times: that time when I was 15 – that time with Anthony at the Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris and then one time at his house in 2008, at his place midtown.

I’ll always remember that moment of seeing Anthony become suddenly incredibly deferential towards this older musician that he’d revered. Just watching that interaction was beautiful. So, Ornette had this way of coming all the way from the end of the hallway… Big airport, right? From far away, you just saw him. And, he wasn’t a big man. He just had this extraordinary presence. Very regal. [Paul] Motian had that too. Not big men. Small men but with size… just incredible charisma and quiet personal charisma. It’s like the solar king arriving from beyond the horizon, it was really an amazing image.

So, yeah, that’s when I moved to New York. I had come back to Paris after being at Wesleyan and having this very intense time with Braxton playing his music. Before that, I was in Paris.

I had actually been visiting my parents who lived in West Hartford. I went to visit them. I was living in Paris and somebody I knew in Minneapolis who played in my teacher’s group there in Minneapolis, Robert Rumbolz, great trumpet player, was getting his PhD in Ethnomusicology at Wesleyan. And, we spoke on the phone, I hadn’t seen him at that point since I was 17, and he said, “Oh, you know, Anthony Braxton is teaching here. You should come in and sit in with the ensemble.”

So, at that time, I was… That must have been in ’92. Summer of ’92. I was 23…24. I sat in on the class and I was really excited. I’d read Forces In Motion and had been listening to Braxton for a long time. He was so incredibly kind and enthusiastic, he stopped the rehearsal in the middle and said “Who are you?” And, then afterwards we spent a couple of hours together. I’d ask him questions and then he told me, “Come back to America. We need musicians like you in America.”

Braxton is like that with young musicians. He makes you reverse all of the doubt and all the insecurities and all the lack of self-confidence and all the discouragement that you’re getting from the environment from being a musician. He just wants to singlehandedly reverse that kind of negative vibe in one moment, in one encounter. And, he does it.

Based on the strength of that conversation, I made the plan to leave France where I’d been living for a few years and had a girlfriend, had a band that I was playing in at that time.

I left the following January and showed up basically on his doorstep at Wesleyan one day, you know, the first day of the Spring semester at his class, which was an incredible class. He was giving the, I think, Ornette-Mingus-Coltrane class or something. I showed up for the first class. He was talking about the Egyptians and mathematics, you know, 3000 years before the birth of Ornette, Mingus, or Coltrane, and then finished by trying to play some Wagner on the record player and then the class ended. It was amazing.

And, then I went to tell him, “I came just like you suggested. I’m here,” and he responded, “Who are you?” In between either I’d grown or shaven off a beard so he didn’t recognize me. I had a moment of panic thinking, “Wow, I made this huge change in my life to come and it’s all based on this conversation which maybe, like to him, hadn’t really meant anything.”

So, anyway, I went to the rehearsal, to the class, and said, “Do you mind if I sit in on the class?” He said, “Okay.” I think he was a little in a bad mood ‘cause of the fiasco with the record player and trying to play Wagner and people walking out. So, then we went and we started playing and he stopped the rehearsal. He exclaimed, “I remember you!” He was so kind. He was just great. I said, “I came to study with you.” He said, “No, no, no. We’re gonna do projects together. If you’d come here three weeks ago, you would have been on this album I just made ”. He’s like that. It was a beautiful thing.

And, so when I first moved to New York, I would go to Middletown, take the bus every Wednesday to play in his standards quartet where he played piano at a place called the Buttonwood Tree. I remember it was with Mario Pavone or Joe Fonda on bass. One time Mario Pavone brought Thomas Chapin in, which kicked my ass, just the way he would play the heads, you know?

Cisco Bradley: So how did you get situated in New York?

Michael Attias: Anyway, that was right around the time of me coming to New York. Fred Lonberg-Holm, the cellist who now lives in Chicago, he was still living in New York. He was a really great friend and a really valuable kind of entryway into a certain scene in New York at the time. Through him I met Anthony Coleman, who I still work with. He has also been a close friend and big inspiration.

It was really a different world at that time. The old Knitting Factory, the one on Houston, was still there. I think my first two New York gigs were at Roulette, the old Roulette, and the old Knitting Factory in Anthony Coleman’s group called the Selfhaters Orchestra. [John] Zorn, [Marc] Ribot, and Elliott Sharp were in the audience. It was a great moment for the downtown scene, that particular downtown scene.

Cisco Bradley: Right. You came in like amidst of the boom.

Michael Attias: There was still the initial generation of the players around Zorn. I mean, Anthony kept on working with Zorn for a few years after that. But, it was kind of like the tail end of that particular moment. Knitting Factory was really an interesting… I had gone to the Knitting Factory before as a listener before moving to New York. Whenever I would visit New York, I saw incredible things there. I saw an Ed Blackwell Benefit for his dialysis treatment where everybody played. I remember Dave Holland playing trio with Steve Coleman and Smitty Smith. Dewey, [Mark] Helias. A lot of people that later I met and got to play with or got to hear in another context. I remember hearing them there.

The Knitting Factory at that time offered a certain cross section of the music, so many different kinds of scenes. They were organizing tours in Europe where people would travel together. William Parker, John Zorn, and Tim Berne and whoever… Jean-Paul Bourelly, Dave Douglas may have been in the same bus together touring in Europe. If not literally at least within a few weeks of each other.

So, it’s kind of an interesting moment to be like in your mid-20s to come to New York and be able to hear a lot of very radically different approaches to some of the same questions and to hear them co-exist there in the same night and the same place. The center was still the East Village. That’s where I lived at first. I lived in different sublets all around the East Village.

Cisco Bradley: Do you know how the Knitting Factory went about setting up tours in Europe?

Michael Attias: How they did it? They had some agents that they worked with and promoters that they worked with in Europe. I don’t know the mechanics— I was too young or too new to the scene to really benefit from that. Somebody should write that history.

Cisco Bradley: But the Knitting Factory felt like it was in their interest to also be promoting these musicians abroad?

Michael Attias: Yeah. So, they would have the Knitting Factory in Europe. There would almost be like a Knitting Factory festival like in Germany or in France or wherever. And, New York has always been of interest to Europe, like what’s happening in New York is a measure of what’s going on in the music, because of the diversity of it. Not that there aren’t other places where great music was happening or, even more so now, I mean that’s much less central. But, it’s still kind of central. With all the criticism of the music scene today in New York and how it’s not what it used to be and so on, it’s still an extraordinary magnet for all kinds of musicians.

For example, you had [Tom] Rainey play here at New Revolution Arts on June 13. I mean, Rainey, in Europe plays in big festivals. He’s a legend. He’s one of the great influences on the music. That’s not a story that I see very often told. In fact, the real story of the music I don’t see it really told very much. Now, it’s more like, you know, the journalists seem to be spokespersons for the PR, for the publicists, because that’s the way that the money is moving. But, I don’t really see an in-depth survey of “What is actually happening? What are the methodologies involved? Where are they coming from? Who was the first one to improvise like this and where did they get it and how did it get passed on to younger generations?”

Cisco Bradley: Yeah, I agree.

Michael Attias: I used to be the always youngest player in any band. Now, I’m sometimes the oldest. And, I get it from that side. Wow, it’s so valuable to play with people who are just super hungry and they are in their early 20s and mid to late 20s. ‘Cause they can really kick your ass. They can really make you question your own assumptions about music. It’s good for you. It’s good for the older players and it’s good for the younger players to be playing with people with more experience.

Cisco Bradley: How did you get going in New York? How did you really get started? I mean, beyond having some support that you already mentioned, were there key encounters that you had with particular people or certain places that you played a lot?

Michael Attias: Well, like I said, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Anthony Coleman, on one hand. On the other, there were people who had studied with Blackwell at Wesleyan and that I’d heard there and whom I started to run into in different sessions.

The main person I’m thinking of is Chris Lightcap, the bass player. I’d seen him play during that semester at Wesleyan. I’d seen him play with a drummer named Gerard Faroux, who had been a Blackwell disciple, who I’d actually heard play at that Blackwell Benefit that I was talking about. That must have been like in ’92. ’91… ’92. Sometime before his death in October ’92.

So, anyway, this drummer had Blackwell’s drums in his apartment on 11th Street (where I later lived) and had exercises that Blackwell had written out and bootlegs with Ornette and stuff. Hearing Ornette the first time on record was… I don’t think I would have felt… enabled, entitled… I wouldn’t have my own personal entryway into being an improviser within this sort of, you know, the large jazz tradition or outside of it if I hadn’t heard The Shape of Jazz to Come. Part of it is because the sound of it connected so much to my own … to the first sounds that I heard.

You know, my family is from Morocco. The first music I ever heard was Arabic music in my grandmother’s house and Jewish Moroccan music which has a lot of similarities. I defy people to tell the difference unless they really know, you know, in a lot of places. There’s a lot of interchange. Anyway, hearing Ornette’s sound and Charlie Haden’s bass on Lonely Woman made me feel, wow, deeply familiar. Just sent goosebumps up my back. Anyway, I had a very intense connection to Ornette’s music. And, hearing these young musicians play that stuff and that drummer play all these Blackwell… All that language was really exciting.

Cisco Bradley: Which drummer?

Michael Attias: Gerard Faroux. He’s a French drummer. Older guy who has passed away now. And, somehow, I ended up playing… Now, this I don’t remember. I ended up playing a session at his place on 11th Street with Chris [Lightcap] and we played some Ornette tunes. And also with a pianist named David Shields. I don’t remember who brought me there, how I got there. But, it was great.

And, Chris and a drummer named Igal Foni, who you might know or not know, he lives here now, he’s a great drummer and musical mind, and he was the first drummer that I wrote for. He was a close associate in Paris, and then when he moved here.. He and Chris and I had a trio that was maybe my first band here. And, we toured, and stuff like that, and recorded. And, that was the core of the record Credo.

Cisco Bradley: Okay. So, that would have been going on in the late ‘90s?

Michael Attias: By the time we recorded Credo, it was ’99. I met Igal in ’92 in Paris, which is where I had my first band, and started recording and playing music professionally. That was in Paris. I played in a Monk tribute then. It was two horns… two saxophones, bass, and drums – The first record that I made was with that group. I can say I was 21…22…23 by the time we recorded. We transcribed Monk’s solos and figured out how to play them without piano. It was very Lacy-inspired in a way. Steve Lacy is a big inspiration.

Cisco Bradley: So, when you arrived in ’94 you were about how old?

Michael Attias: I was born in the summer of 68.

Cisco Bradley: And, then, how did things evolve from there? You recorded your first New York record, Credo, right?

Michael Attias: Well, I was working a day job. I was trying to survive. I worked for nine years in the French bookstore at Rockefeller Center, kind of managed the French Literature section. It was great. I love books. But, it was also really grueling. I mean, it went from being 35-hour a week or 40-hour a week and days got more and more chopped off as I got busier as a musician – writing so much music, playing with as many different people as I could.

And, I was already kind of not in a particular scene. I was curious about very different things. There was a real disjunct between some of the things that I was interested in and what I was actually playing.

Cisco Bradley: Were you playing music outside of the jazz spectrum?

Michael Attias: Yeah, I was really interested in Latin music. I started going up to Boys Harbor in Spanish Harlem and sitting in with the rehearsal bands there on baritone. That was very important for me because I’d been working with Braxton playing duo with him, playing in his large ensembles, also playing standards with him on piano quartet. So, doing a lot of different things. However, I didn’t realize some of the things that I was missing in terms of foundational musicianship and certain relationships to rhythm and time that I hadn’t developed. But, at the same time, I thought I could read anything ‘cause I was reading all sorts of hard gnarly music.

And, then I showed up to a Latin band rehearsal and it’s all written in cut time or 4/4 with quarter notes and half notes, a few eighth notes here and there. You know, after looking at charts of 13 over 2s, 17 [making sound], you know, this looked like, oh, cool. But I swear, the first fifteen minutes of the rehearsal, I couldn’t place a single note. ‘Cause, just the relationship of mark on paper to beat, to time, to sound, to ensemble was different. And, it was very deep, very profound, the incredible lineage that’s behind like what beat 3 is, and how it relates to clave. I’m self-taught, really, as a musician so, which means that I had developed some things to a pretty advanced level precociously and, then had other things that were way behind just because of what you get exposed to and what you don’t get exposed to.

So, at that point, I felt like I really need to do a lot more homework and start to examine certain fundamentals that I had sort of skipped in my impatience to immediately get to that zone of creative music that I love so much.

Cisco Bradley: So, you were playing baritone as well a lot—

Michael Attias: Yeah, I was playing a lot of baritone. I was playing baritone in the Selfhaters bamd with Anthony Coleman. Anthony, whom I’m gonna be playing with soon, he’s both well known and unknown. It’s kinda interesting. Great musician. He really shook me up. Really shook up a lot of things, a lot of assumptions that I had about creative music.

He’s very, very specific about certain things that I had never thought about, you know, register, his specificity of register. Things that if you’re just coming from jazz or free jazz, you tend of just for granted or you’re a little bit vague about. And, also, just how things sound as opposed to the concept that’s behind them. Or, the process, what does it actually sound like?

And, he has a really corrosive sense of humor that would take things that I revered and suddenly just flip them around and make them comical in a good way. I didn’t and I don’t always agree but, the questions that come from him are extremely valuable.

So, yeah, I was kind of like all over the place and trying to re-learn how to play my instrument. There’s a little bit of a shock. I think I’ve spoken to a lot of people about this. Or, a lot of people have spoken to me about this – about how they come to New York from somewhere else then it’s a shock. It’s a trauma in that way. There’s something traumatic about it and suddenly they stop writing, for example. For a lot, they just can’t write music anymore. Others, it’s something else. But, yeah, something shocking and some people have to leave and others stay.

But, I know for me, I was used to having time to rehearse with my friends and life was so much easier in that way in Paris. And, here, suddenly well, if you get one rehearsal, you’re lucky and you don’t have that kind of leisure of like going over parts calling, “Oh, can we try this? Can we do it this way?” It just wasn’t like that.

Cisco Bradley: What does that do to the creative process?

Michael Attias: On one hand, it’s very stimulating and, on the other hand, it can paralyze you, depending on where you’re coming from. Suddenly you realize there are hundreds of other people who are into the same things that you are into and who are trying to do maybe the same thing. Whereas before, where you were coming from, there weren’t. You were the only one. I mean, now, it’s a little different because the information is so available. I guess it’s different now. But, for me, when I was young, I didn’t know anybody else into Ayler who was my age. Or, into Dolphy or Charlie Parker or King Oliver for that matter.

Cisco Bradley: So, was the next thing that you ended up working on RENKU?

Michael Attias: In between I had a sextet that grew out of the Credo album.

Cisco Bradley: Michael Attias Sextet?

Michael Attias: Mm-hmmm. The Credo album grew out of the core of that trio of Chris Lightcap and Igal Foni, which is a collective in which we played all of our tunes and Ornette Coleman covers and different things.

And, then we had a tour in Israel and… Reut Regev. Do you know Reut? Trombonist?

Cisco Bradley: Right.

Michael Attias: Okay. So, that’s when Igal met Reut. They’re married. She was amazing. We played with her and a clarinetist named Harold Rubin. We had a tour in ’95 or ’96. And, then music just grew from there. I was writing more and more. I got back into my vibe of composing and writing for that group as a quartet.

And, then I met Mark Taylor, the French horn player who’d done so many things. I think he’d just stopped playing with Threadgill at that point. He was in Very Very Circus. And worked with Max Roach, Abdullah Ibrahim, etc. We met in a rock band. He was really encouraging. Really cool. And, then Sam Bardfeld, the violinist, and I were playing in other groups. I started hearing the French horn-violin combination. The trio became a sextet with the addition of the trombone, the French horn and the violin. I think half of Credo is that group. And, we kept on playing after that. I started writing, in a way, like harder and harder music for that group. I started working with Satoshi [Takeishi] around that time.

The music got harder and harder and less manageable for me in a way and I began to really miss improvising with the trio that had been the core of the sextet. I really started to miss that. So, I formed a trio with Satoshi and John Hebert, whom I’d been playing with in a different group.

Cisco Bradley: How did it lead you to those two people?

Michael Attias: John, I met in Edward Ratliff’s group, which is also where I met Sam [Bardfeld]. I don’t know, I think I did some sessions with him and would hear him play. Yeah, I loved his playing. Beautiful sound. I met Sean Conly— I met him I think as he came in subbing for John in that group, in Edward Ratliff’s band. Edward Ratliff I met through Fred Lonberg-Holm. That was the first band that I was in — one of the first bands that I was in in New York was called Peep and we played in the Knitting Factory a lot. Our record came out on that label.

A lot of people I met around that time, some I still work with and some I don’t. Ahmed El-Motassem. I did arrangements for, an Egyptian singer. Really interesting. Kind of an underground legend in New York. I love that guy. So, those kind of things.

What can I say? I mean New York… you know, being in the East Village, going to the Punjabi stand, eating that food while listening to Bollywood music, buying all kinds of tapes, getting all these constant juxtapositions between high music, low music, pop music – blurring all those boundaries, music from different cultures. It’s surreal, crossing the whole world in a single night. That’s another thing about New York that I think is so attractive. That’s maybe a little bit disappearing. But just the intensity and the richness and the density of the textures here, you know, walking down the streets, all the different kinds of food you can taste and experience. Go to Queens, Queens is still like that. You go to Jackson Heights, it’s incredible.

That sense of things. That was a super big inspiration. And, the musicians that I like to work with were really into that. Are really into going and discovering these things and tasting them. Yeah, I don’t know if young musicians are quite getting that. They’re coming to a New York that’s a little bit more sterile and white-washed. That diversity was super exciting. Being able to play like— you know, going and hearing like different groups and playing different kinds of music. Paris didn’t have that at all for me.

Cisco Bradley: So, did you find you were sort of incorporating lots of that into your compositions as well as the way that you improvise?

Michael Attias: Yeah. You are what you eat. It comes out. Either by embracing it or by rejecting it. Another way that one reacts to that is by looking for purity. I mean, you have incredibly austere improvisation going on in New York too. I wonder sometimes if it’s a reaction to that – to that profusion of diversity and all that information and so people get attracted to having some things extremely pure and minimal. There are different ways of processing. That becomes part of who you are as an artist – is how you process it – how you treat it, how you filter it.

Cisco Bradley: So, you formed RENKU and—

Michael Attias: Yeah, just to play. To really be able to play. And, I feel like those guys taught me how to play– you know, Satoshi and John. Or to play in a new way.

Cisco Bradley: What do you mean by that?

Michael Attias: It was both super exhilarating and uncomfortable. How they felt time, how they would allude to it in the form. This ability to have the form inside of you, completely internalized, and then not play it. You know, I couldn’t treat them like a regular rhythm section. It wasn’t about me soloing on top of like some kind of groove or support that they’re providing me. Sometimes they would pull the rug out from under me.

So, they taught me to be self-sufficient – to generate my own sense of the harmony and the time and the forms whether open or not. Also, both of them really made me rethink the distinction between what is written and improvised – where does the form begin, where does it end. They really expanded my sense of that.

I think John, very early, said something to me like, it sounds so simple but it’s a profound readjustment to really take it in. He said something like the piece begins with the first sound and it ends with the last. So it’s not like it’s free and then we’re playing some written material that we’re gonna nail and then we’re gonna play free or we’re gonna play on the form. It’s much more integrated. For a lot of us, it comes from listening to the second Miles Davis quintet where the form itself becomes a parameter of improvisation. It’s fluid that way. It’s a moment. There’s the first sound – which is not necessarily the first note of what is written. It might be what precedes it or it might be the last note of what’s written or it might be starting somewhere in the middle of it and then finding your way to the next part or finding your way backwards and listening. This kind of intense interactive listening.

Cisco Bradley: And, so is that only possible after playing a lot together?

Michael Attias: That was the first gig. There was no rehearsal. We showed up at Barbès and did it. I wrote one tune on the way to the gig, which we later recorded. They could read anything. They could internalize everything so quickly.

I think we did a quick sound check and I remember John saying, “Okay, well, this is gonna be cool.” And, he started calling people to see if anybody was gonna come to the gig. And, it was great. And, that was it. That was so exciting for me. It still is. I mean, it’s still really exciting to play with them … and challenging. I just played with John at Cornelia Street [Café] on Sunday night. We were both sidemen in a group. He played an unaccompanied introduction to a piece that he’d barely seen. We barely rehearsed it, just a few days before that, and it was amazing. Organic development. It’s not about rehearsal or not rehearsal. How you’re living your life is your preparation for the next note that you play and that might include a rehearsal or it might not. But, whatever it is, you have to be ready. And, having rehearsed doesn’t exempt you from having to be ready for the wholly unexpected thing that can happen.

Cisco Bradley: You just have to build your instincts and stay very alert while you’re playing?

Michael Attias: Constantly. Yeah, alert, open … I think there’s a story that’s not being told – is that story of how people are doing that. How that’s evolved out of the way that several generations of musicians in New York have taken in Ornette, Cecil [Taylor], Paul Bley, Ligeti, Led Zeppelin, whoever. All of these things and how it’s formed a way of listening and a way of being with each other as human beings and as players. I think there’s something there, you know?

Cisco Bradley: Yeah. How would someone write about that? I think it’s a very difficult…

Michael Attias: Just fucking pay attention! I mean, there was one week a few years ago I heard Rainey, I heard Jeff Davis, I heard Nasheet [Waits], and I heard Motian all in the same week at Cornelia Street [Café] or somewhere around there playing small door gigs, right? I mentioned Jeff because he’s like a much younger musician who’s influenced by Rainey and Motian and all of these people. And, I thought wow, where is the story about this? It’s state of the art drumming. New York now. What other city in the world has four consecutive nights can have such total masters in completely different groups? There’s no way you would mistake any of their universes for each other. I mean, they’re absolutely singular, you know, Nasheet, Paul, Tom…

Why isn’t that a story? I mean, it would be a story in another country that actually valued its own culture. It’s American culture. It’s in this incredible state of refinement. I have to say, the best gigs that I’ve seen, the most meaningful, I haven’t seen any journalist. Certainly no publicists. And, whenever I do see a publicist at a gig they’re on their cellphone posting about it instead of listening. So, what the fuck is going on? You know, instead, it’s just like PR, PR…

On the other hand, I remember being at one gig of a saxophonist where I was the only audience member that was a civilian. Well, I’m still a musician. But, there was a record producer, a publicist, and two journalists. You know, and the music was okay. It’s fine. But I was thinking “What’s going on?” Where’s the Martin Williams of our time? Where are they? Whitney Balliett, Leonard Feather. I don’t even like some of those guys. But, they were paying attention. They were coming up with things that I don’t necessarily agree with but they were asking questions. Martin Williams going to Ornette’s rehearsals, going to Paul Bley/ Jimmy Giuffre/Steve Swallow’s rehearsals when they had 2-3 people in the audience but, he still found it valuable to go and, you know look at the scores and try to suss out the practice of how they relate to the sounds he’s hearing. — Okay, so how does this work? How do you do this? You can see it in his book, the collections of articles. Wow! Instead of just branding and connaisseurship.

Cisco Bradley: Do you want to talk about it now? ‘Cause I was gonna come back to that to the end as we kinda like—

Michael Attias: Oh, sure. Yeah. I mean, it’s more like in general when you see articles about the music, it’s rare that you feel that the important questions are being asked. And, unfortunately, it shapes the music because then you have musicians who wanna make sure that they’re gonna get the coverage in those outlets. And, we start to feel like the music is already starting to gear itself towards the description that’s gonna be given of it later.

Cisco Bradley: You’re right. It’s a problem.

Michael Attias: That’s why I was mentioning Rainey. Rainey is a good example. But, there are many. All the young drummers, maybe two generations at this point of … two waves of drummers now already have grown up listening to Rainey. Not that he’s old. He’s like the youngest drummer in the world, in some ways. And, [Paul] Motian. So, that information has shaped their way of listening and knowing what’s possible. Maybe they don’t even know that some of the things they’re doing he made possible. In the way that Rainey took in Jack DeJohnette, Paul Motian, you know, whoever, Max Roach, Bernard Purdie, Tony Williams … How he processed all of these things. Has somebody written about the influence of Tom Rainey on generations of musicians? Not just drummers. How he deals with time and development. Rainey helped shape Tim Berne’s bands. Helias’ Open Loose is another one that he profoundly shaped. And, I’m pretty Tim and Mark would tell you exactly that. They would not be the same without him. But, Tom’s way of shaping thematic material, of improvising towards an arrival point– There are all these things that are now kind of taken for granted as the way that people deal with material and improvise together.

It doesn’t necessarily exist in other places. I go in like a different city with musicians from there, unless they’ve checked out New York music, they don’t necessarily know how to do that or understand even that that’s what’s going on. They may be doing other things that I don’t understand. There’s that too. But, at this point, he’s been in the world for a while, like all over the world, playing. And, a lot of the groups that he’s been in have been very influential.

Cisco Bradley: Everyone has a certain uniqueness to them but I agree that Tom Rainey just lives in his own universe in terms of the way that he sounds, the way that he influences other people when he plays.

Michael Attias: Yeah. He doesn’t talk about it but, he can. If you push him, like tell you how he’s thinking about the time, how he’s thinking about grid versus open space versus … It sounds musicological but, that’s what I mean, that… It should be discussed in some way, not an academic way but in a way that if you’re talking about the music, I mean that’s what you’re talking about. If you’re not talking about that, then it’s something else.

Cisco Bradley: Would you like to talk a little bit about about RENKU?

Michael Attias: So, RENKU … Let’s say 10 years? Our first gig was 2004. First record was recorded in 2005, came out in 2006. The one you’re holding in your hand, RENKU IN COIMBRA, we did in Portugal in 2008. We’ve recorded since then but nothing’s come out. And, then you have this CDR that I made of the new album, which I hope somebody’s gonna pick up, which I think is our best one. I think it’s the strongest one yet.

Cisco Bradley: Can you talk about how the group has evolved in terms of both your relationships through each other as musicians but also kind of how the music has evolved and how your strategies for improvising have evolved in your approach to composing for these musicians who you now know incredibly well?

Michael Attias: I’ve really come to learn how little I need to write. It’s sort of the crucible … the laboratory. It’s the alchemist’s chamber or something – that group, for me. It’s a laboratory. Whenever I’m thinking about whatever is happening musically in my life, in a way it always comes through that group. Comes through and then I learn something about it. I hope it’s something like that for them too.

We’ve been playing since 2004 but in New York, that doesn’t really mean that we’ve played a lot. We’ve only had one real tour in all that time. Part of it is because I’m not great at being a businessman and making tours happen and all that.

But, in a way, there’s something nice about that because it means that we may not play for six months and then when we come together, there’s all this new information of what’s happened since then, in the last six months. It’s like old friends, you know, you check in. And, it also creates— we never get comfortable, in a way. It never becomes a static thing where I can say well, this is the sound of the band. From the first time we played we had a sound as a band, but it’s very natural. It evolves naturally according to where we are. And, gigs can be very, very different from each other.

If there’s any model for that in terms of a relationship, I think John named it a long time ago he said something about going to hear Frisell, Lovano, and Motian, “Well, one day it’ll be like that for us.” Not that we’ll be as great as them but just in the sense that years and years of playing together, of having that kind of musical relationship where so much doesn’t need to be said. I think the first few years we hardly talked. We barely rehearsed. We didn’t even talk about what we were doing. Which for me was very different than for example, the experience in Paris where you would really talk about everything, talk and listen together and do post-mortems. None of that.

It was a school for me in that sense too – of just letting the music evolve naturally and organically, not forcing things. They both have this amazing gift. They’re masters of the craft of making the craft disappear. It’s very hard to locate the moment that they make a decision because it just feels so inevitable and so natural and so organic to the music making.

Of course they are making decisions but, the decision that is at the root of something that you hear in the moment and which blows you away, that decision might have been taken 10 minutes ago, completely undercover, you know what I mean? It’s like a secret that’s kept and just grows under the surface, which is beyond your grasp, and then it’s suddenly there and you don’t know where it came from but it feels absolutely natural that it’s there.

That’s kind of how we all play together. When I listen to the recordings I go, “Oh, wow. Okay, that’s happening.” I can hear that happening between us. So, how it’s evolved is that, for me at least… I’ve come to understand more and more that that’s the focus of that band and that it’s— anything can go through it. It’s like a process. It’s not a sound. It’s a process. It’s an organism that can take in whatever material. I’ve brought in bossa nova tunes to that band. It can be anything.

RENKU, the piece itself, which is on the first album, is one of the most metrically-challenging things that I’ve written to improvise on.

Cisco Bradley: Can you explain that?

Michael Attias: Yeah. Well, do you know what a renku is? A renku is a form of collaborative poetry, Japanese poetry. It was a scholar’s game where poets would sit together and each improvise a haiku, so following strict prosodic rules of five syllables – seven syllables – five syllables. It’s three lines. And, then there would be two joining, linking lines of seven syllables each which would then connect to the next haiku that someone else would compose.

So, it’s an improvised, collaborative form of Japanese poetry following extremely strict prosodic rules. And, haiku, I mean is the registering of an illumination.

I’ve always been interested in numbers, in the sensuality of numbers and how it inform everything. It just forms itself like the morphology of the world. All these forms— Why is it that your fingerprints, the spirals of your fingerprints are similar to a whirlpool or to the Milky Way. Or, when you look at a tree, you’re looking at the bark and you start to see that there are patterns or forces in the way that water flows which repeat themselves in a different scale and different kinds of material and different natural phenomenon. It’s so mysterious. It’s so amazing.

I think the first time that I connected to it, in the sense of art too, was seeing the da Vinci painting of The Virgin on the Rocks. And, you look at it and you see that the line that he’s using to draw goes through every material that’s been represented. So, it’s her hair, it’s the thread of her dress, it’s the veins of the rock of like the actual rock that she’s sitting by, it’s in the leaves. The way that he painted that is such a grasp, an intuition of what the universe is made out of, of these patterned energies. Patterned energies that express themselves through matter, that organize matter. What Buckminster Fuller called self-interfering patterned integrities. Patterned energies that form a knot for example… You take one end of the rope and you make a loop and you pull the other end of the rope through it and there you have a knot. And, we can understand the material that is in front of you by the way we grasp that sense of self-interfering patterned integrity, whether that rope is made out of Manila or hemp or fiber or rubber, or nothing at all just like now I made a knot out of words but you saw it just the same. And, our bodies are like that and the universe is like that.

So, RENKU, the band, hopefully is like that. Like whatever material is there, moves through the process of the three of us playing together. I guess what we’re trying to do is get out of the way as naturally as possible. And, then just by listening and feeling things and being really true to how your body moves. Satoshi can take the sound of something falling down the stairs and he hears it as music, like he hears that rhythm. There’s something so natural about what he plays.

I think John and Satoshi are masters of the grid. They understand the grid very well and so then they can play off of it and start shaping and inflecting it. So, RENKU, the piece… so, like I said, 5-7-5-7-7, right? Haiku is 5-7-5 then this linking lines of 7-7 – is the metric template for that piece. It works on the level of the eighth note, but also of the slower rhythmic sub-divisions and also numbers of bars. It’s 31 bars.

And, there are different ways of thinking about it. So, like that pattern, those pattern of numbers, the way that they move… the 5-7-5-7-7 are also happening in the eighth notes. So, you have like this moving across. Also 5-7-5-7-7 is happening in the quarter note and also the bar structure— So, it’s all moving at the same time at different speeds. That’s the mathematical basis of it.

But, what’s interesting to me is I put it in front of John and Satoshi and they just make it feel so natural. I think those numbers … I don’t think you could just take any numbers and do that. I think there’s a reason why that Japanese form, that prosody, feels natural and is right. Those numbers have a way of interacting with each other that’s true to some kind of breath construction, some kind of construction of breath.

Cisco Bradley: So, those are like deeply innate in people or something?

Michael Attias: Yeah. Something about that rhythm feels just right. The 31, right? ‘Cause I mean 30 , 5 times 6, you can think of it in different ways. And, then there’s that extra 1 that makes it move forward, that gives it that momentum to go. So, it’s tumbling over itself.

So, you know, we learned. It was this challenging thing, the bass part is really challenging, with all these different kind of levels of melodies happening. The intervals are also a bit based on fifths and sevenths so, the 5-7-5 is happening intervalically too and I’m mixing it with some sixths, alternating major and minor…

I’m kind of inventing my own musical theory for the piece, which is kind of a constant thing in my writing and my composition I think since I started writing music, which is as soon as I knew how to make a note on a piece of paper, I wanted to compose, you know, just randomly or not randomly.

But, that I always wanted each piece to have its own kind of universe of rules, its own musical theory in a sense, which then I would never use for another piece again. You break the mold. That’s it.

I’m not gonna write RENKU the sequel or whatever. That particular form belongs to that.

There’s a form of Provençal poetry that some troubadours wrote in Troubadour, the 12th century where you would have a strophe, a stanza… that would follow a pattern of rhymes and assonances and irregular line lengths in terms of syllables that would be specific to that particular song. That strophic structure would never be repeated in another canzon. One of those strophes became the sonnet – the 14 line-sonnet. It was originally just one of these things would have been one of kind but, then people got lazy and they started reusing the stanzas and, eventually, you get this kind of hardened forms, you know?

I think the blues too originally… you know, like Lightnin’ Hopkins and… even Muddy Waters, it’s not always this 12-bar blues. Rollin and Tumblin by Muddy Waters has 5 ½ bar phrases . John Lee Hooker is not playing 4-bar blues a lot of the time. Robert Johnson, there’s something like a recurrent measure of 3/4 in his Kind Hearted Woman Blues. And then, the example of Andrew Hill, Herbie Nichols, Monk in a tune like Criss-Cross or Coming on the Hudson …

It’s interesting. I’m really into that specificity of form to, to that..

Cisco Bradley: And, then try to explore in different… In each piece you started exploring different…

Michael Attias: Yeah, a different set of rules or constraints that I make for myself. And, it’s that tension between that and then something very physical and intuitive and improvised. How do those relate to each other. How did they either fuse and make something that’s very blended. Or, how did they fight against each other. Sometimes the tension between them is really interesting.

So, that RENKU, you have that metric construction, which is very strict and could be rigid and, then I wrote this kind of solo across one chorus, which a very asymmetrical ornate version of the same rules but turned into almost like a Dolphy kind of exploded line, you know

On the new recording, … Yeah, I like that we recorded RENKU again. It’s a live album. I wanted to record a live version. The studio version is… it’s like we’re still learning it anyway. It’s different. This is a few years later, how has that sound evolved.

Cisco Bradley: You talked about getting out of the way, allowing it to happen. How does one do that? Is it something you had to work on together or is it something that you all understood in a certain way already when you started?

Michael Attias: We didn’t have to talk about that because I think each of them do that on their own. Like I said, they transmitted it to me. But, yeah, I think it’s something that’s in common for a lot of the players. This idea that if you’re really focusing on the listening, on listening to what’s happening, and you don’t get in the way of how you react to it or what you’re doing, you just shift the focus more to what you’re taking in, then things can happen more quickly and more precisely and more spontaneously and more naturally.

But, I think athletes do the same thing. I was watching this thing, ’cause John, he’s gonna play a solo set on this residency at Ibeam and he mentioned that he wanted to dedicate his set to LeBron James. And, he and Ralph are always talking about basketball. So, imagine, if LeBron had to think about what he was going to do, there’s no way he could do it. I mean, it’s extraordinary what he does. Just faking out one player, making him think that he’s gonna throw the ball over there and then suddenly he just passes it in the opposite direction without even looking. And, he knows where the other guy is gonna be who catches it. If you’re using your brain and your conscious mind, you’re extremely limited because we have senses everywhere. So, if you’re just really present and really alive and really in the moment and in your body and in your ears and you’re not into extraneous, unimportant image stuff… you know, when you’re really there, you’re out of your own way. You can just be. To be strong and comfortable. Like I said, alert, to use that word. Aware. And, using your conscious and unconscious and every part of you activated.

To me, that’s one answer to the question of why play music or why do anything if not to reach a kind of higher and more complete form of being in the world, in the moment, that’s using more of your faculties. If you’re just using you’re calculating rational mind, that’s only very small part of how you can experience the world.

But, to really experience it in every way, like to taste, to smell the music… When you’re out of your way, you taste the music. You’re hearing it with your eyes, you’re seeing it with your ears, you’re smelling it. It’s tactile. It’s a complete experience.

At that moment, then you’re reaching… yeah, you’re out of your way and you can just let yourself be. And, then that’s when you see a concert and say, “Wow, how the fuck did they do that?” because everything is engaged and everybody’s doing that together – One kind of unified mind.

Cisco Bradley: So, sort of that approach has carried you through the three records that you’ve recorded?

Michael Attias: Yeah. RENKU IN COIMBRA, was a very special circumstance. Right before leaving for Portugal, up to the morning of taking the plane to go to Portugal and doing this, I’d been working with Paul Motian. We did the Vanguard for a week and then went into the studio for two days. The second day, I think I went that morning straight to the airport to fly to Portugal, to Lisbon, did a rehearsal there that night with Portuguese musicians and, then we started this residency in Coimbra with the Twines of Colesion quintet.

Originally, w when I did the quintet, this quintet with Malaby and Russ Lossing, I called it Renku +2, but then it felt like after a couple of gigs it felt like it was its own entity, its own thing and that it should have its own name.

So, that’s the band that we set out to record, the quintet. We played three nights in this club in Coimbra and then we played two or three more gigs in Portugal. And, on the afternoon of the second day in Coimbra , John, Satoshi, and I recorded the trio album. And, that was I think the shortest recording session I’ve had. I think we did it in two hours. It was so much fun.

One of the songs on that album is from, you’ll hear it, one of those nights. It’s an excerpt. The one that’s called Fenix Culprit, you can hear Russ Lossing on that one because it was recorded at night– It’s an excerpt from a performance of the quintet. I felt like it flowed nicely and it was kind of surprising to have that piano suddenly come out of nowhere. I loved that band with Tony and Russ. It was really exciting.

Cisco Bradley: Is this still active now?

Michael Attias: No. I mean it could be but we haven’t played in a long time. I still play with Tony. I consider Tony also an inspiration and influence on me. Somebody that kind of shook me up.

Cisco Bradley: In what way?

Michael Attias: Just the level of his improvisation, of his playing, of everything. Like in a band like Open Loose, I remember when I started hearing Open Loose, Mark Helias’ band, just to hear the degree of interaction, of listening, of what they could achieve. It’s remarkable. There’s no other band that does that. So many people have tried to do that in a way, but Tony did it so effortlessly.

Tony’s saxophone playing is incredible. His conception of the sound of the saxophone in ensemble, it’s something that I felt very close to.

When we started playing together, it just felt so incredibly easy and natural to me. All of this play with the materiality of the sound itself. To be more succinct, there were things that he brought together in his playing that for me came from very different parts of my own life and personality and experience, and which he was able to blend pretty seamlessly. At some point, your influences as a musician it’s not any longer just the records that you listen to. At first, it’s the records that you listen to, you know, in your formative years. But, then more and more the influence becomes the people whom you work with, the people that you’re close to. Though deeply grounded in Jazz and all kinds of dance music, Tony had also obviously listened to European improvisers. The really sound-based players. You know, Evan Parker and others, he had gotten his own take on that. On how to manipulate the sound of the saxophone, how to create, how to paint with it, how to get really involved into all the different kinds of texture and materiality and density and making the saxophone sound not like a saxophone but like something in nature.

Another thing of Tony’s that’s very influential for me and I think other people too is how to improvise with a rhythm section without being a soloist and how to shift the focus of the listener. You might not know that it’s happening but somehow he’s also shaping the focus of the listening so that even though he’s playing, you’re actually listening to what the drummer is doing or the bass player or the pianist or whatever other instruments. How he’s able to inhabit different layers of the music from middle ground to foreground to background and, shift from them sometimes on the dot, you know, from moment to moment. Tony has this classically-based technique, the intonation. The love for that, for blending. All of those things that are so important in so-called free improvising. It’s easy to forget– lose sense of.

So, he sets a very high standard for that that I really appreciate and is inspiring for me to reach for them. The beauty. Some sense of beauty. Some sense of being able to control the instrument and breathe through it and be relaxed. All of those things.

And, also, he’s very encouraging. When he played stuff that I wrote, he was always super encouraging. He’d tell me that my music made him feel high. Because there are so many layers going on and he wouldn’t know which one is the top.

That was always a big thing for me in large ensembles, this attraction to total polyphony and having the harmony come from the moment to moment intersection of all of these lines that are equal, democratically equal, to each other. So, that there isn’t a lead main line. It’s obscured or those roles can shift. I’ve always been super attracted to that since I was a kid.

Cisco Bradley: Yeah. So, do you want to talk about Spun Tree?

Michael Attias: Spun Tree was kind of a healing project for me in a sense that at the time I’d been through personal upheavals and was kind of in a dark place, living under a dark cloud and then suddenly imagining writing for trumpet, for that sound, Ralph’s sound, and the sound of the alto and the trumpet together, had the joy, the heraldic joy I needed to come back out into the sun. Maybe ’cause, like I told you, The Shape of Jazz To Come was kind of my way in for myself.

Even though I loved a lot of other music, I’d never felt like there was any place for me in it. Whereas The Shape of Jazz to Come, Ornette’s sound in that band, suddenly make me feel, oh, I can… There’s a place for me in this. Not to sound like them but that it’s a permission or it opens a door.

So, the alto-trumpet sound, Bird and Diz or Fats or Miles, Eric Dolphy and Booker Little or Freddie Hubbard, Ornette and Don Cherry – Jackie McLean and Lee Morgan or KD. It goes on and on. There is something about that sensibility. That sound, it’s always been meaningful to me but I think meaningful in the history of jazz. That sound is radical. It’s a traditional sound but it’s a traditional radical sound or something. Like with bebop, that sound was a call to arms, a call for revolution.

There is something about wide open space rhythm, the Midwest. I became a musician in the Midwest, the musician that I am. My family moved from Paris to Minneapolis when I was 9 and I started playing saxophone there. And, even though it’s not a long time, the years from the age of 9 to 17 are really, really important. It’s those years that I spent there and the first music that I heard live that got me thinking about this. Something about that sound that I associate with the Midwest too, with America – the alto/trumpet.

So, I wrote this song Spun Tree. It’s so positive. There’s something about the sound of that piece that just heralded something from me that was gonna be positive and that was gonna be good. And, that’s really what that record came out of.

At first it was a quartet with Ralph, Tom, and Sean and, I got excited about writing again, writing more specific things, writing different kinds of things than I had then, for them. Such amazing musicians, you know, all three of those guys. We played a few gigs. We played at Vision Festival as a quartet.

And, the writing, I kept on having to sacrifice certain things because there wasn’t an instrument to play them. Certain ideas just were not coming through. And I realized what I needed was a piano. And, not just any piano. I got together with Matt Mitchell. We did a session. I think his career was just starting to explode. I mean he was already playing with Tim. I hadn’t heard Snakeoil. He’d contacted me coming from Philadelphia wanting to meet people and so on. We did a couple sessions and it was, okay, this is it! And, so I added him to the group and we recorded pretty soon after that.

So, it’s the right combination of something that had been playing for a couple of years, and then something completely fresh. I think we started playing in 2009 and we… Matt started playing in the band at the end of 2011. We recorded in April of 2012 and it came out that year. I’m really proud of that album. It’s also that it’s an album. It’s really conceived of as an album. It’s different from how we sounded live even at the time.

It was a great day in the studio and mixing it and working on it and putting it together. I felt like as a composer I really was able to say what I wanted to say but, mostly, I was able to do it in a way that invited each of the players there to really be themselves. I love Ralph on this record. I feel he sounds totally like himself. Somehow there’s a compositional unity, and at the same time, it’s totally their record too. And, that’s a hard thing to get. It’s a hard balance to find.

Cisco Bradley: It’s one of my favorite of your recordings.

Michael Attias: Thank you. So, we’re gonna be playing a couple of times at this residency and playing all new material. I hope people will come!

Cisco Bradley: Can’t wait!

–Cisco Bradley, July 9, 2015

1 comment

Join the conversationMichael Attias Interview « Avant Music News - July 10, 2015

[…] From Jazz Right Now: […]

Comments are closed.