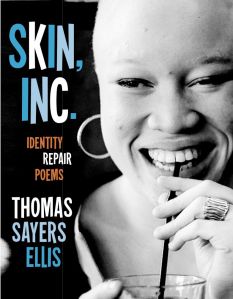

Poet, photographer, professor, and bandleader Thomas Sayers Ellis is the author of The Maverick Room and Skin, Inc.: Identity Repair Poems (Graywolf Press). His poems have appeared in numerous literary journals and anthologies including The Paris Review, Poetry, The Nation, Tin House and the Best American Poetry (2007, 2011, 2010 and 2015). He has been a fellow at the MacDowell Colony and Yaddo and is a recipient of The Whiting Writers’ Award. His photographs have appeared on numerous book covers, and in 2011 his images on the vanishing musical culture in Washington, D.C., were exhibited in a one-person show titled Unlock it: The Percussive People in the GoGo Pocket as well as in “DC As I See It” at the Leica Gallery in Washington, D.C. During his early years he was a percussionist on the DC GoGo Scene and, in 2013, he performed a short stint with Burnt Sugar. A controversial and percussive figure who is also known as a literary activist, in 2015 Ellis was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship for poetry.

In 2013 he co-founded (with saxophonist James Brandon Lewis) Heroes Are Gang Leaders (HAGL), a band of poets and jazz musicians dedicated to the sound extensions of literary text and original noise. Between 2014 and 2016 HAGL recorded The Amiri Baraka Sessions (an unreleased two CD project) and released The Avant-Age Garde I AMs of the Gal Luxury and Highest Engines Near / Near Higher Engineers. This Fall HAGL will release Flukum, an original project dedicated to Etheridge Knight and Ntozake Shange.

Here is a clip of a recent live performance at JACK, June 7, 2016:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-OHYV1ds8E&w=560&h=315]

Interview

Cisco Bradley: HAGL came together after the passing of poet Amiri Baraka. Can you talk about your relationship with Baraka, his influence on you as an artist, and what you see as the most profound aspects of his continued legacy today?

Thomas Sayers Ellis: In many ways no one artist of influence can guide another artist to wholeness, so––in that way––Amiri Baraka’s work is, simply, a branch on the tree of the Tradition (and by The Tradition I mean, the Black, African American, American literary treasure chest of exchanges, rhetorical strategies for survival, and the way in which an artist has to continue (not just inherit) language, expression and life. It is possible, as you know, to be an artist and never attend to any of these responsibilities or behaviors. In fact the literary world is full of educated persons who avoid the nitty-gritty feet-march ground-work of folk commitment. Baraka, on the other hand, was a very thick branch in the collective aesthetic ammo. And he “be” that whether you agreed with him or not. He even invited his own language, and by that I mean a system of sounds and attitudes that progressed inward and onward (throughout his work) toward changing meaning. I knew him and respected him but never worshipped him; the greats can sniff out ass-kissing. I hosted him in the Dark Room Reading Series, read him, made sure I heard him whenever I could, read with him, collected his work, passed out his work and studied the way he was received and treated within the community and outside of it. His journey through forms and phrasing as well as his practice of turning political tension into creative energy, song and nuance were remarkable. Before we chose the name Heroes Are Gang Leaders (taken from Tales by LeRoi Jones) for The Amiri Baraka Sessions, we almost called ourselves Baraka’s Shoes. The most profound aspect of his legacy, well, the one we’ve inherited is the one that says “Don’t believe shit unless you can feel it” which is really relevant today now that frequency control and many other ways of weaponizing everything are hijacking feelings. Folks don’t know what to feel anymore or whether or not the integrity in what they are feeling is genuine. The Baraka approach of immediacy and action in the Art Act is under fire and will place a target on your back––a real ass one, off stage, not a staged one, onstage.

CB: How did HAGL come together as a band? What kinds of conversations has the group had internally about Baraka’s legacy that have shaped the creative process? What other major intellectual influences do you see present in HAGL? What do you see as the major artistic influences on HAGL?

TSE: HAGL is clearly influenced by all of the things, in life and art, that every member of HAGL comes in contact with and desires to come in contact with. Arrivals and departures. That’s the chore––to find musicians/poets who can access “all the possibility” (Aimé Cesaire) and to create and recreate the atmosphere that will allow such unknowable forth-going. HAGL has been fortunate to have something different happen every time we step into the studio and on stage. HAGL had been able to do this without having subject-matter or artistic concerns dictated to it. Even when we kick our own laws to curb, the kick contains meals of Togetherness. This is rare today because the majority of artists are all talking about the same things or trapped in the closed circle of always creating and auditioning from news and for fame, to sound good. We want to sound like HAGL. Is there “good” in the sound of that? HAGL might just be the branch of Good Destroyers many folks need but are afraid to want. Heru Shabaka-ra (aka Ryan T. Frazier), our trumpet player, says he’s a villain. And Villains Are Gang Leaders. And when I listen to him lead us through “Hurt Cult,” I re-wonder.

CB: Where would you place HAGL in terms of genre?

TSE: HAGL is everything-not-yet-but-still-coming because who knows where creative breathing begins and never ends. If you list every known genre, HAGL is scratching the pleasurable itch at the edge of the problematic real estate between gene, genre and generosity. I mean we like to cook on all of those stoves at once, then control it, then free it, then leave it alone. It’s weird but we are, in terms of genre, wherever the ear has no fear. I could list my musical interests. I could tell you what I hear in each HAGL member and what I accept and reject from (of them) from the other bands they play in. In that way HAGL is made up of the slices of exploration one must reach for when one has something to say and something to sound about the world. I’m too inside HAGL to name a genre because I am also inside HAGL surrounded by the saboteurs of genre. Has HAGL defined HAGL yet, definitely not yes not.

CB: What can you tell us about The Amiri Baraka Sessions? Can you describe HAGL’s creative process in approaching Baraka’s work?

TSE: Being a poet and having been around the voices and books and lives of poets for years, you know which individual aesthetic practices are rooted where, so I simply gathered a few poets who I thought, already had within them, a kinship to the Black Arts Movement capable of revisiting it and extending it––without fear of it and without the fear of the now-folks that fear it. To this end I, initially, chose poets Randall Horton and Mariahadessa Ekere Tallie. We also needed a white, female poet to update with honesty, toughness, progressive privilege and desire-racism the role of Lula from the play Dutchman (1964) so I asked poet, professor Ailish Hopper to write for the session––after which she stayed on and joined HAGL. James found the musicians but I asked poet Janice Lowe to play keyboards. Janice and I co-founded (with Sharan Strange) the Dark Room Collective, a Black Writer’s group and workshop (in Cambridge, Massachusetts) in 1988. We did The Baraka Project in four sessions and, once Margaret Morris joined, we went back in two extra times to add voices and to eventually record “The Tender Arrival of Outsane Midget Booker Ts Who Kill Drums Running Da Voodoo Down,” “Sad Dictator,” “Superstar,” “Le AutoRoiOraphy” and “WeWeWeWe the Remarkable” (for Gwendolyn Brooks). I consider this period to be the first Golden Age of HAGL. “Golden” as in magnificent, creative outbursts. We were super productive and the ideas just wouldn’t stop. It took time to gel. The first Baraka session we used Michael Bisio on bass and I wasn’t sure if HAGL was possible until I heard the recording of “The Shrimpy Grits” from that session. I think I would have gotten out had there not been any spark. We had a violinist, Gwen Laster, and Tyehimba Jess, a poet, playing harmonica. I was open to not having the project be a TSE poetry vehicle, so when James and I randomly ran into Tracie Morris near Port Authority, we invited her to the second Baraka Session and she laid down three tracks none one of which, due to space, actually made the final project but heped to shape an aspect of the HAGL effort. We used Dominic Fragman on drums for that first Baraka Session too. Luke Stewart (bass) and Warren ”Trae” Crudup (drums) didn’t join till the second session. During that second session we recorded “Land Back” which features Ekere doing two poems by Amina Baraka (Amiri’s wife), one of which is for Pharaoh Sanders. We needed the 60s/70s anthem urgency musical march and she delivered. It was joyous, togetherness work. At the end of the song I try and update Baraka’s “I Liked Us Better.” We stretched it out on “Land Back,” a door had been opened. I wish I could say that I had, during this period, a schematic creative process but nothing works for me like reading. I was reading Baraka, re-collecting him, re remembering him. I could feel him around me and I kept whatever James was doing musically near me. I was a visiting professor at Wesleyan University, so I had a lot of travel time on the train––time I used to get rid of the mental barriers in me between the music and the poems. I never want HAGL to be the kind of group known for easily laying poems on top of jazz songs, never. We try to invent the knowable from the unknown need to know every time we take it to the stage. We all agree on that––though some of us would like to be freer. I’m always asking James Brandon Lewis (JBL) what he’s working on and, often, most of my text come wrapped in grooves, word and sound as one. Like JBL says, “TSE is a groover!” I am. Some of the poets and musicians we invited to the Baraka Sessions that, for once reason or another, didn’t make it are: Ursula Rucker, Airea Matthews, Matthew Shipp, Vijay Iyer, Chelsea Adewunmi, David Henderson, Michael Veal and Ras Baraka. I absorbed Amiri, so I didn’t really need a process. Process is me. I am process…at this point. I would be riding the train leaving Brooklyn and get a call from JBL about cancellations and just open my notebook and fill in the gaps with the Amiri I was carrying around in me. He’s one of our most internal echoes. No hiding place allowed.

CB: HAGL released its first record, The Avant-Age Garde I AMs of the Gal Luxury, in 2015, and its second record, Highest Engines Near/Near Higher Engineers in 2016. Could you talk about what each of these records represents artistically and how the group has evolved and grown over the past two years?

TSE: The first record The Avant-Age Garde I AMs of the Gal Luxury, was us proving HAGL had more in the tank than The Amiri Baraka Sessions. Remember we came together just to pay tribute but while we were paying tribute to Baraka, via his work, we were born. And as the personnel decided on it’s self, the compositions and ideas just kept coming, so we moved––in a literary sense––to Bob Kaufman, but no way where we going o do another two-cd song book. I knew in my heart that we had to do his famous poem “Would You Wear My Eyes” but I didn’t want to plan it too much, just take the general idea and allow whatever we were going through to guide us. I was teaching at Naropa for a week in the summer program and there was a studio there, compliments of Ambrose Bye, that we could use. I had a raw draft of a poem in my notebook that I had written as a loose criticism of all things “Experimental.” And miraculously, our week in Boulder turned to the kind of thematic exploration that created a new sound for HAGL. We spent two visits in the one-room studio, no booths with barely anything written down. I was worried but I learned to trust the band…I will always trust the band…now. That project is us breaking away from us, because we could have easily called it quits after The Amiri Baraka Sessions. That two-cd unreleased project is full and remarkably engineered.

Back in NYC, while were mixing and adding trumpet and a few extra lines of poetry to The Avant-Age Garde I AMs of the Gal Luxury, we began the project that would become our second record Highest Engines Near/Near Higher Engineers. I wanted to move a bit more away from any dependence on literary text but, while I was living in Montana the idea for a Gwendolyn Brooks inspired poem-song wouldn’t stop worrying me––the problem of how to take her small but very powerful poem “We Real Cool” and turn it into an anthem, a widescreen sonic one, that gathered in her name, her literary landscape and lineage. I wanted this song to know it was a Gwendolyn Brooks song-poem and to be in love with other Gwendolyn Brooks song-poems. It had to have many movable parts and it had to have its own system of seasons. I wanted the lister to hear the climates change in the poem-song, and I wanted it to be teacher-ly without being preachy, so guess what we threw the classroom in, a Chicago Literary Roll Call, a sermon, a revolt-like March and a lit crit lecture. It’s also so chill that by the time it become the Power Object that it is, the listener forgets how it began, so we begin again!

I was still determined to prove to the band that I trusted it musically and that not every HAGL poem-song had to be a slave to TSE’s notion of pattern and groove. This is how we ended up with Final Vinyl, a 48 minute poem-song. We sat in the bedroom-studio on MacDougal and let it flow. Of course I stood in the center of it all dancing and pointing and directing but the band felt it’s way through that original composition which owes a lot of love to the talents of the whole crew. I will say that it was the first time in a long time that James Brandon Lewis called me before a session full of excitement about a having received a particular arrangement in his body the night before. For a brief moment the song was called “African Dream” because James was still reading Bob Kaufman but I had moved one and knew that it needed its own vision. I was scared of it when I first took the track home. I knew it would consume me––morning, day and night. I knew it would take away from the other areas of my life that needed attending to––too late, I was all in and I could hear just where Randall Horton and I could do something together that would stand. I wanted Highest Engines Near/Near Higher Engineers to be a smart record that was also unpredictable and an unpredictable record that you could remember. Highest Engines Near/Near Higher Engineers snatched us away from sounding like we were in a studio and proved that we were just opening the tin can of trying any damn thing we wanted to. We were open books not closing them. I am proud of it despite the seemingly foreshadowing of so much coming change. On “Final Vinyl” we get all spiral ritual (not Spiritual) in our own way. Thus the free energy lyric as homage to Tesla-style creativity.

CB: I recall reading that Bob Kaufman performed his works orally and often did not write them down. Did you find Kaufman’s sense of oration and orality one that allowed his poems to transfer to music readily?

TSE: I guess if we could, truly, measure musicality in a poem–by comparison to other poems––and by comparison to itself or rather the idea of movement in a line versus the idea of music in a sentence…and where the poet places the breathing within the breathing and where the poet breaks both meaning and breathing…If we could do that and then consider, too, the con game of subject-matter––meaning because Bob Kaufman wrote about jazz many of us, by that fact alone, slightly and blindly convinced that he is more musical. The, if you add his “Hip Thang” and his “Original Beat Thang” and his “Surrealist Thang,” well then one need not lift a finger at all to express or translate his orality to song because all of those aspects, which could be traps, are all already there just screaming for usage…I think had we had time to think about it we would have run in the other direction and trued to do Kaufman boring, stripped, and full of anti-Jazz as in without Jazz as in “No More Jazz” which Kaufman was wise enough to build into his oeuvre, so that was the best place to begin…in cacophony and defiance…knowing we had to also return to something musically introspective and Adult. We got unlucky-lucky. Lucky Margaret and I were having a bad time not getting along and lucky James was carried around a song in his notebook from Graduate School that he had no intention of using but the moment I heard it, I knew it was our main sound for a new way of thinking about Kaufman. In JBL’s notebook the time was called “for a time,” but––in the studio––I cut the lights off, total Blackness, and had him and Luke Stewart lay down the instrumental that would become Dem Damn Beatitudes which also served as the first step in editing and organizing the energy of what would become Would You Wear My Eyes which is sort of an extended honest and brutal alternate extended take off Dem Damn Beatitudes. Since Kaufman took a vow of silence we did Dem as an instrumental, no words, and since he spoke later in life we did the extended version with vocals. After hearing our version of Would You Wear My Eyes, I voted not to include it on the CD but JBL sad it was the realist thing on the CD and that it had to stay…Im also sure I cried while were making it and I would never listen to it now…even when we tried to perform it live, I cut it short. I’d leave the room when it came on while we were mixing it. That was a very tough period but also a very fertile creative period. I feel like I was being given the best world and the worst world all at once. And I guess we left it all in the studio that day. Exhausting. Remember we made that CD in one open room, no booths and barely enough mics and headphones.

CB: What new direction does Flukum represent for HAGL? What other developments do you see on the horizon for the band?

TSE: We went from the 2 CD project The Baraka Sessions to a long tribute to Gwendolyn Brooks to gigging live together to The Avant-Age Garde I Ams of the Gal Luxury to Poetry Mind Control, the collaboration song with and for Anne Waldman to Highest Engines Near / Near Higher Engineers to and through Flukum all in less than two years, so at the end of Highest…James and I and Margaret (as I recall) were already feeling the need for a break or a hiatus but Flukum came rushing through me so I followed it, re-reading Etheridge Knight, I wanted to walk away but couldn’t. I was teaching, preparing to go to Iowa, and trying to hold a band together that was scattered from NYC to DC, a band of members who all played in other bands. It would have all been impossible had we not had a place like the apartment-studio-bedroom at 47 MacDougal to record and gather and eat and chill and fall asleep in. Without a doubt, the HAGL narrative––for better or worse––would not be as musically full were it not for Ambrose Bye (our engineer) who never closed his doors to us. And who served as an amazing and guiding set of critical eyes and ears. Ambrose says it’s not possible for a HAGL CD to not be HAGL prophetic. And I think he’s 100 percent right, I also think Flukum is HAGL’s crossover CD and its swan song to HAGL’s first era of growth. Flukum is HAGL’s most self reflective and social critical commentary yet and we try to do it while dancing and driving (our own way of using the drummer) straight through the body of Jazz. Where The Avant-Age… and Highest Engines Near…were vast branched explorations, Flukum attempts to be the full tree offering a full meal . In other words HAGL has heard everything that’s been said about HAGL and HAGL ain’t afraid of HAGL. Art is our only illegal system and, beyond Hurt Cult, we are not finished breaking shit aka we still got shit to drop!

CB: What can you tell us about The Amiri Baraka Sessions? Can you describe HAGL’s creative process in approaching Baraka’s work?

TSE: Being a poet and being around the voices of poets for years, you know which individual aesthetic practices have rooted where, so I simply gathered a few poets who I thought, already had within them, a kinship to the Black Arts Movement capable of revisiting it and extending it. To this end I chose poets Randall Horton and Ekere Tallie. We also needed a white female poet to update with honesty, toughness, progressive privilege and desire racism the role of Lula from the play Dutchman so I asked poet, professor Ailish Hopper to write for the session. After which she stayed on and joined HAGL. James found the musicians but I asked poet Janice Lowe to play keyboards. Janice and I co-founded (with Sharan Strange) the The Dark Room Collective, a Black Writer’s group and workshop (in Cambridge, Massachusetts) in 1988. We did The Baraka Project in four sessions and went back in two extra times to add voices and to record “The Tender Arrival of Outsane Midget Booker Ts Who Kill Drums Running Da Voodoo Down,” “Sad Dictator,” “Superstar,” “Le AutoRoiOraphy” and “WeWeWeWe the Remarkable” (for Gwendolyn Brooks) once Margaret Morris joined. I feel like this is the first Golden Age of HAGL. We were supper productive and the ideas just wouldn’t stopped. It took time to gel. The first Baraka session we used Michael Bisio on bass and I wasn’t sure if HAGL was possible until I heard the recording of “The Shrimpy Grits” from that session. I think i would have gotten out had there not been any spark. We had a violinist, Gwen Laster, and Tyehimba Jess, a poet, playing harmonica. I was open to not having the project be a TSE poetry vehicle, so when James and I randomly ran into Tracie Morris near Port Authority, we invited her to the second Baraka Session and she laid down three tracks none one of which, due to space, actually made the final project. We used Dominic Fragman on drums for that first Baraka Session too. Luke (bass) and Trae (drums) didn’t join till the second session. During that second session we recorded “Land Back” which features Ekere doing two poems by Amina Baraka (Amiri’s wife), one of which was for Pharaoh Sanders. We needed the 60s/70s anthem urgency musical march. At the end of the song I try and update Baraka’s “I Liked Us Better.” We stretched it out on Land Back, a door had been opened. I wish i could say that I had, during this period, a schematic creative process but nothing works for me like reading. I was reading Baraka, re-collecting him, re remembering him. I could feel him al around me and I kept whatever James was doing musically near me. I was a visiting professor at Wesleyan, so I had a lot of travel time on the train––time I used to get rid of the mental barriers in me between the music and the poems. I never want HAGL to be the kind of gout that just lays a poem on top of a jazz song, never. We try to invent the unknown from the known every time we take it to the stage. We all agree on that. Im always asking JBL what he’s working in and, often, most of my text come wrapped in grooves. Like JBL says, “TSE is a groover! I am. Some of the poets and musicians we invited to the Baraka Sessions that, for once reason or another, didn’t make it are: Ursula Rucker, Airea Matthews, Matthew Shipp, Vijay Iyer, Chelsea Adewunmi, David Henderson, Michael Veal and Ras Baraka. I absorbed Amiri, so I didn’t really need a creative process so to speak. I would be on the train leaving Brooklyn and get a call from JBL about cancellations and just open my note book and fill in the gaps with the Amiri I was carrying around in me. He’s one of our longest echoes. No hiding.

CB: How has HAGL managed to balance all of the voices involved in the creation process? What has each member of the group contributed to this process? (I know membership has fluctuated, so just focus on the current members if you wish)

TSE: I have a lot of voices in my head and I have tried to (only) choose personnel with their own many voices that are different from the ones in my head. It’s really about listening. I listen to all of the members of HAGL I may ask one of them to write something for a track and the result will be too written, and then I will be within earshot of a conversation between band members and hear the full spoken text of what we need––already natural and already fully realized. My job is to know just where it goes and how else we might weave the next thing we want to say from it. Of course the material has to be relevant, creatively and social relevant. I am challenging myself now, in post-production for Flukum, the new record, as to how to make the line “Beat Juice Excited” mean more than what’s there. It’s also true that voices that are comfortable with each other will often nicely blend in terms of timing and substance. I’m glad HAGL hasn’t had the problem of vocalist that sound like strangers to one another or that sound like perfect damn friends. I don’t believe in “tension” in poetry but I don’t mind allowing “tension” in the recording studio.

CB: What contributions do you see HAGL making to the contemporary discourse about #blacklivesmatter and as commentary on the culture and politics of the new civil rights movement?

TSE: HAGL is funded by HAGL, no smoke screens or green screens or Controlled Opposition within the organization, well––not anymore. We know what matters. And we won’t allow competing versions of history or sponsored struggle to trick us into any kind of bad art, war, cultural propaganda, etc. We are older in our breathing than BLM. We march out in front of them not from the rear. We have come to correct quite a few Civil Wrongs, including the okee doke and freedom rope-a-dope.

I

We play

the platters

II

that matter

and that’s all

III

that matters,

not your

IV

alma

mater.

CB: Thank you!

–Cisco Bradley, August 11, 2016