Tilt Brass managed to fill the Pioneer Works performance space with sound and people in Red Hook on October 12th. Their performance was the 12th in a monthly series called False Harmonics put on by Pioneer Works highlighting new improvisational music. Tilt Brass, an ensemble led by trombonist and composer Chris McIntyre, performed pieces by Phill Niblock, Julius Eastman and harpist Zeena Parkins who also performed and conducted one of her own works.

The evening began with a 1977 composition by Julius Eastman called “If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?” Chris McIntyre transcribed this complex piece from a recording from Buffalo, New York, by the Brooklyn Philharmonia. Characteristic of Eastman’s work, “If You’re So Smart” contained both humorous and bitingly acerbic elements. Moments of trombone flatulence followed long tracts of deliberate ascending and descending chromatics. Measured horn ascents were occasionally punctuated by tolling bells. About halfway through the 20 minute performance, violinist Josh Henderson took a plaintive solo composed of repeating two-note intervals creating a building tension that did not resolve. Henderson’s solo was followed by more horn chromatics and the open trombone tones that reflected the cheeky title of the piece. Eastman’s approach to creating “organic” music was on display in this lengthy composition. The initially separate elements evolve over the duration of the work, combining and condensing to form the multilayered whole. McIntyre mentioned this would be his last Eastman transcription, but it was far from his first. The composer and arranger has transcribed and performed a number of other Eastman compositions both with Tilt Brass and his previous ensemble Ne(x)tworks.

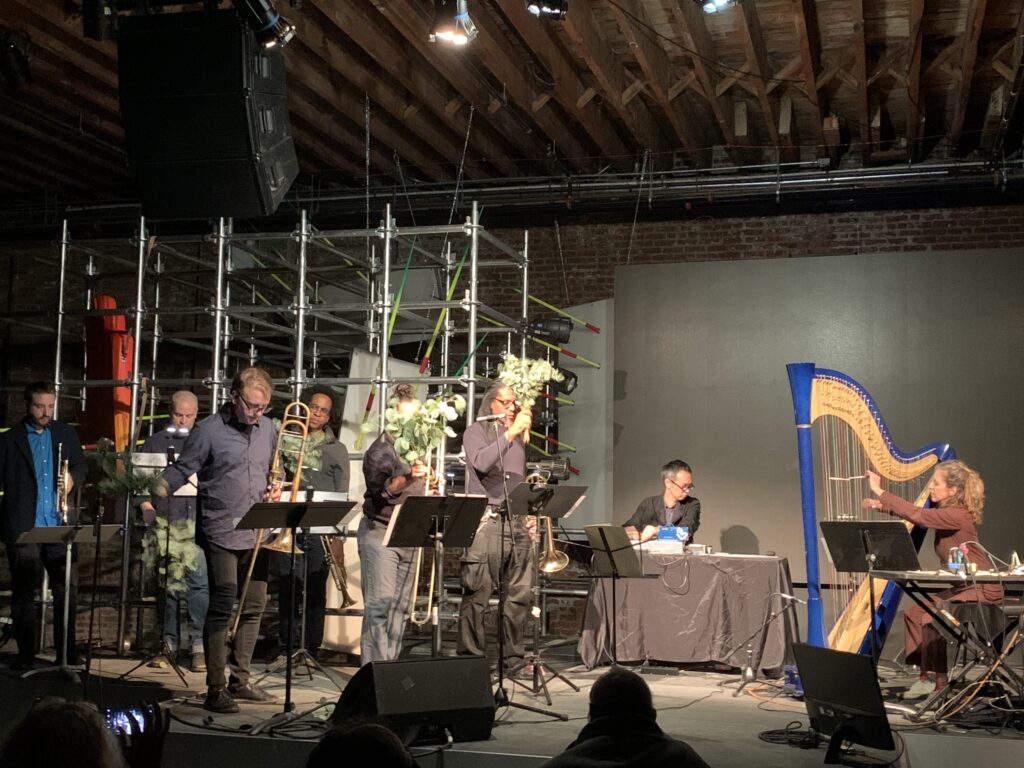

Pioneering harpist Zeena Parkins was next up, performing one of her own original compositions and another solo piece composed by John Mills. Parkins employed her signature intensely tactile approach to the instrument throughout, displaying the exciting combination of electro acoustics she is well-known for employing with Thurston Moore, Bjork, and others. Percussive and erratic, she banged and plucked, thrummed and slapped the strings for her solo piece that also involved pre-recorded processed sounds triggered through her laptop. She employed various implements including a red ribbon for dampening, a few plastic sticks for resonance, and aluminum mallets to activate a wide sonic range for the strings at her disposal. She conducted six musicians from the Tilt Brass ensemble to perform her “Whistling in the Dark Wind.” For this piece Parkins shuttled back and forth between conducting and eliciting punctuated tones from her harp, interrupting the brass with trills and dampened chords. Meanwhile James Fei, positioned at the rear of the stage, looped, and reprocessed the sounds via analog synthesizers. Suddenly, against the backdrop of synthesized horn harmonics, each musician picked up a hefty bunch of eucalyptus leaves and agitated them in unison creating a kind of organic static reminiscent of a windy white noise.

Photo by Hillary Carelli-Donnell

The final and standout piece was Phill Niblock’s impressive work, “Exploratory (Rhine Version, Looking For Daniel)” from 2019. Thirteen Tilt Brass musicians scattered themselves about the audience and held sustained notes generating a Niblock-ian drone for just over 23 minutes. After some brief research I found out that Niblock spent his early years working with choreographer and dancer Eliane Summers at Judson Church in the 1960s. This helps contextualize Exploratory’s choreographed movement-based elements. The horn players roved about the space in a semi-fluid manner, agglomerating and disbanding in an intentional yet evolving way. Before the sound began, audience members were also encouraged to float and wander around the space. The simplicity of the single droning notes allowed for the emergence of rich tonality as each musician played stalwartly through the few distinct tones in Niblock’s composition. Audience members took slow measured steps through the space or sat listening with eyes closed. Niblock’s durational composition encouraged deep listening and turning inward even as the unconventional choreography unsettled the initial arrangement of the space. Posted near the stage was a black screen with a timer starting at 00:00. When the timer reached 23:05 the last lingering tones of the final trumpet faded away into a few moments of silence. McIntyre directed the audience’s attention to the composer, who sat in his wheelchair. Niblock, who had turned 89 the week before the performance, appeared content, as though the audience had just wished him the happiest of birthdays.