Merriam-Webster defines evocation in the following way:

a. the summoning of a spirit

b. imaginative recreation

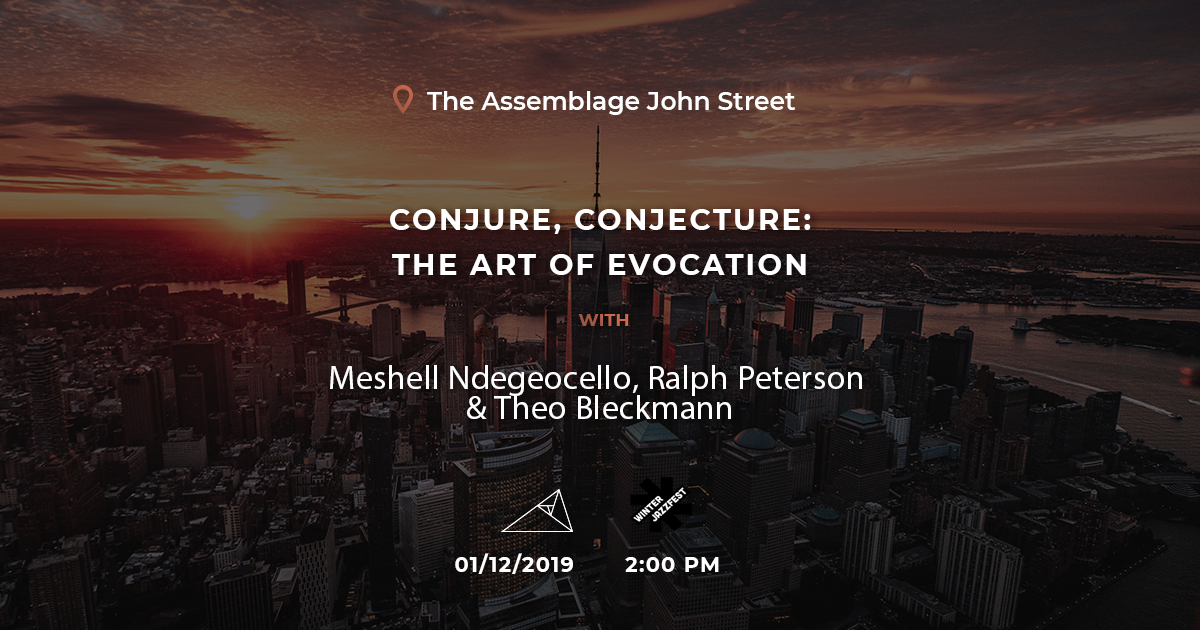

Many of us would agree that at least one reason we listen to music is to escape the mundanity of the everyday. But how often do we consider the possibility of using it as a tool to access ancestral wisdom? The final day of 2019’s Winter Jazz Fest Marathon began at a financial district hotel and co-working space called the Assemblage John Street. Gathered in front of woven mandala tapestries and looking out onto a small but attentive crowd, three Winter Jazz artists converged to examine the concept of musical Evocation. Convened by Nate Chinen, NPR jazz critic and author of the new book Playing Changes: Jazz for the New Century, the panel was comprised of Jazz Messenger drummer Ralph Peterson, Jr., vocalist Theo Bleckmann and Winter Jazz Fest artist-in-residence Me’Shell Ndegeocello. Though coming from rather different musical wheelhouses, each of them shared the experience of having masterfully paid tribute to another artist in their own body of work. Peterson, Bleckmann and Ndegeocello have memorialized Art Blakey, Kate Bush, Nina Simone and Prince, just to name a few. No small feat when we consider the immense cultural relevance of each of these figures.

Consider, for example, Nina Simone. How might an admiring musician manage to access her artistic presence and pay homage to one of the most beloved songbooks in popular music, while avoiding hagiography? Many tributes fail to strike this delicate balance. Indeed most are subject to the Madame Tussaud-effect. The copy may achieve startling similarities, but it lacks the visceral power that enlivened the original and, by extension, its listeners. Think of it like this: You can talk to the wax version of Prince all you want, but good luck getting him to speak back.

When Chinen put this question to the panel, they replied with near unanimity that the conscious mind is only partly responsible for a good tribute album, suggesting that paying homage without necromancing it is not an entirely deliberate process. Ndegeocello said of her version of Simone’s “4 Women”, “Since she’s [Simone] no longer in the material world one has to ‘remember’ to bring those four stories to life, and not experience it as a memory.” “It’s not a conscious thought,” she continued. Here Ndegeocello suggests that the fine line between emulation and hyper-referencing is drawn out with at least as much grace as intention. Later, Ralph Peterson expressed a similar sentiment. Peterson’s forthcoming release with his Messenger Legacy band will pay tribute to the work of Art Blakey. Having studied and played with Blakey, Peterson knew the man as well as the musician. Gruff and disciplined as a mentor and bandleader, Blakey told a young Peterson to show up at 2 p.m. for rehearsal. Peterson arrived promptly at 2 p.m., but Art didn’t show up until 8 o’clock that evening. Peterson recalled, “The first thing he did was point at me and ask one of the guys in the band “Was he on time?”’ Peterson remembers Art as a mentor and, like many others, as a musical genius or as he put it “a load bearing pillar of the jazz world”. At the height of his playing, Peterson said he is always trying to reach a crucial point of relaxation. In that moment, Peterson told the crowd that he is able to “stop trying to play like Art, and just allow the gratitude of the experience to let Art flow through me.” With a vigorous nod, Peterson confirmed Chinen’s inquiry about whether a spirit connection is essential to his most evocative moments of music making.

In his journals, Nobel laureate Andre Gide described all great art as sharing a sort of “density” or “weight”. Elsewhere, saxophonist Joe Henderson noted that jazz listeners are most attracted to music in instances where there is “evidence of some serious information gathering at one point.” If we understand music as a means to access the realm of shared consciousness — where a host of creativity resides — we can better understand the significance of Ralph Peterson’s statement. Jazz as a musical form has its roots in a process of sacred information transfer and conservation. Culturally specific knowledge was carried from the African subcontinent to the Americas through the ring shouts that occurred in fields across the South and Southeastern U.S. and, in particular, in Congo Square, in New Orleans, where enslaved people gathered to evoke and worship the spirits of ancestors and gods. These ring shouts preserved artifacts of cultural memory that the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the African diaspora might have otherwise destroyed, and reformulated these memories into an amalgamated cultural product drawn from pan-African spirituality. Although, contemporary jazz has become increasingly obsessed with the technical aspects of the music — partly due to its classification as a subject of study in academic settings — its value as a tool for accessing spiritual realms is not lost on anyone who has listened to the music of John or Alice Coltrane.

This may have been what Bheki Mseleku, a South African pianist was referring to in a 1995 episode of Talkin’ Jazz, when he echoed Peterson’s earlier comments. “Even though I have a technical limitation,” Mseleku said, referring to his amputated finger as a result of a childhood accident, “I need to become more open to allow more of the spirit come through.”

Me’Shell Ndegeocello speaking at Winter Jazz Fest, 2019. Photo by Hillary Donnell.

It took some time, though, for what we now recognize as “jazz” to emerge from field hollers and ring shouts, and it was by no means an inevitable or linear process. But by the late 19th Century, jazz had emerged into a recognizable form. The industrial revolution had robbed modernity of its god and replaced it with the machine. The movement of people from small towns to booming cities searching for industrial work had caused a widespread sense of dislocation, social alienation and a need for a renewed moral and spiritual connection. Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm writes: “There is no understanding the arts in the later nineteenth century without a sense of this social demand that they should act as all-purpose suppliers of spiritual contents to the most materialist of civilizations.” In 19th-century New Orleans, the people’s use for spirituality was to be made all the more acute by the harsh realities of life in a booming port city at the mouth of the Mississippi.

In 1880, a black New Orleanian could only expect to live about thirty-six years, and a black infant had only a 35 percent chance of becoming a black adolescent. On average, New Orleans had a mortality rate 56 percent higher than the nation as a whole. Burials and homegoings were facts of monthly (if not weekly) life. The jazz funerals parading down Basin Street served as a means of connection to the realm of the departed, allowing celebrants to integrate their experiences of death through ritualized processions which honored and mourned, but also exalted and celebrated survival. In the speakeasies of Storyville, Louis Armstrong’s childhood neighborhood, jazz offered an improvisational space to experience joy amidst near constant suffering and offered opportunities for black New Orleanians to reclaim a sense of power and agency as originators of a new cultural form. Musical expression had a pragmatic mission “to drive the blues away..but also to evoke an ambiance of Dionysian revelry in the process,” wrote blues theoretician Albert Murray. “The music itself,” he said “was equipment for living.”

It should come as no surprise then that on that afternoon Ndegeocello referred to her 2012 project Pour une Âme Souveraine: A Dedication to Nina Simone as a form of “ancestor worship.” Listening to this contemplative, almost brooding album invites us to hear Nina Simone’s energetic output as it must appear to Ndegeocello. At some moments this renders it unrecognizable as part of Simone’s oeuvre. The album reads like an offering, wrought with care and attention and laid upon the altar. Nina is there, but so is Me’Shell at her most meditative. There is sense of their co-presence on this album.

Ever one to eschew classifications, Ndegeocello articulated her idea of what makes music a powerful medium in an interview for NPR when she said, “There’s no hierarchy in suffering. I think the songs that are transcendent are the ones where everyone can feel something from it, you know?” During times dominated by regimes that reinforce injustice and rule by coercion, the function of art which evokes feelings of interconnectedness is far from luxury, it is a necessity.