The year was 1994. I’d already been collecting records for several years and making beats since the late 1980s. I was pretty fortunate as a 14-year-old to have had so much rich musical exposure at that point. This was before Hip-Hop had gotten terrible and early enough that you could still find relatively rare Jazz for affordable, even cheap, prices (way before the gentrification of the record game). The back of some Hip-Hop records had sampled material listed on them also. As much as producers and DJs alike would have loved to keep their sounds secret, there was a point when new jacks such as myself could get basic beginners info straight from the public source.

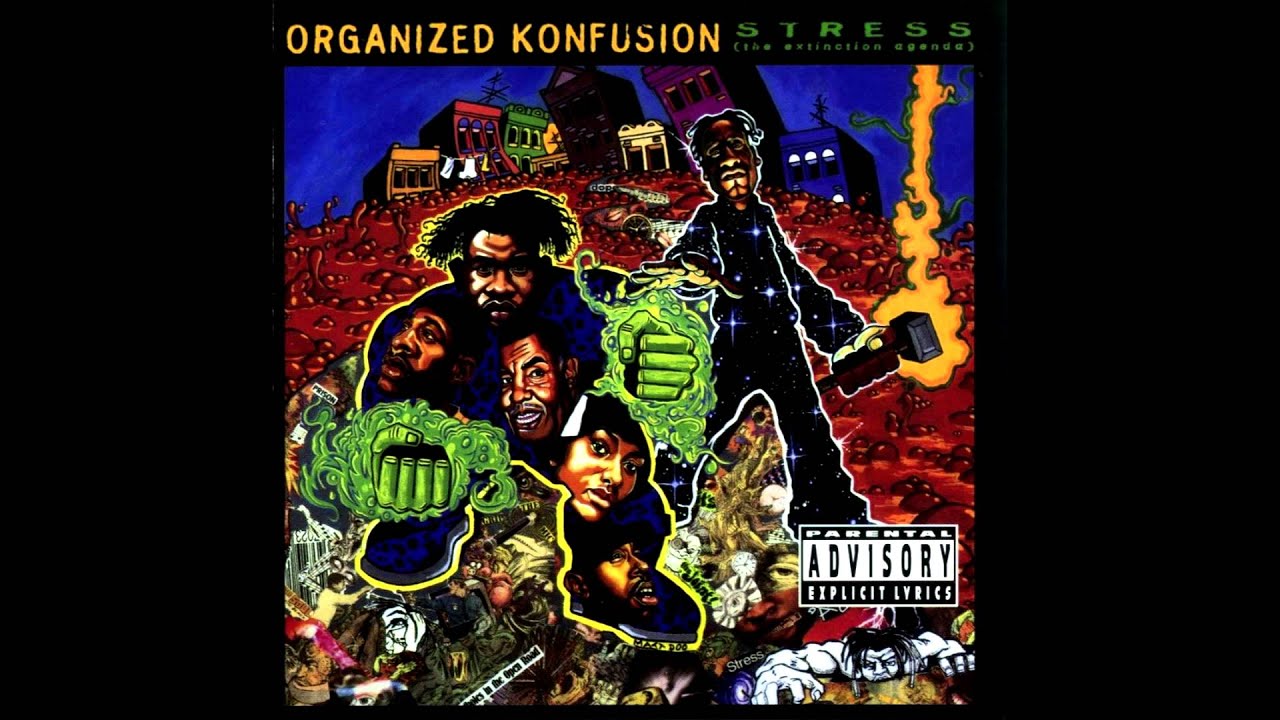

There was a 12” that changed the game for me that year. I’d already been familiar with Organized Konfusion since the release of “Fudge Pudge” (featuring future D.I.T.C. member O.C.). Their rapid delivery and hypnotic production had been the closest thing to Ultra Mag’s Critical Beatdown that many had heard up until that point. Yet, it was “Stress” that made the biggest impact on my 14-year-old ears. Opening with one of the darkest bass lines around, the low-mixed blaring horns sealed the deal on the far-reaching history lesson for me. Back in those days, it was pretty hard to tell what part of a song came from what record listed. So when I flipped the record over and saw a listing for “Mingus Fingus No. 2” by Charles Mingus I was a bit perplexed. The tune sampled an electric bass, and I’d known Mingus as an upright man (I had only seen pictures of him at this point, I think). So it wasn’t until years later that I found a copy of Mingus’ Pre-Bird (Mercury, 1960) that it all made sense. Though Hip-Hop might’ve been my introduction into discovering Mingus, Pre-Bird was not the first LP I’d listen to by the master.

A lot of music came my way between the release of “Stress” and my discovering part of its source material. It was probably back when Impulse! Records had started reissuing several of their big titles in the late 1990s that I saw a fresh copy of Mingus’ Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (Impulse!, 1963). The LP bombarded me. The solo introduction alone proved to be a revelation and quite familiar (DJ Premier of Gang Starr had made great use of this portion of the LP). I’d never heard such clusters coming from a record before. Part Duke Ellington, part Ornette (I thought at the time), part church, and part orchestra; all of these things were immediately present in Charles’ music. From Mingus (x 5) I moved on to the solo piano jawn. Mingus Plays Piano (Spontaneous Compositions And Improvisations) (Impulse!, 1964) was a completely different experience. A man alone with his deepest creative motives, this LP exposed Mingus like a genius at work. Well known as a virtuosic bassist, it also gave light to him as a great pianist (he’d recorded on the instrument before, but not to such devastating effect). At this point, I’d found a new musical hero. Large Professor and Mingus stood side by side as an artist who I’d purchase every LP I could find by them.

Fast forward to 2018.

A few days after my 38th birthday I was in conversation with my good brother Amir Abdullah. This cat has been a huge influence throughout the years and I cannot state enough that my record collection would be much smaller without the work of him and Christian “Kon” Taylor. Their On Track series not only gave nameless context to samples used by known and unknown Hip-Hop artists, but it also helped me think about the larger context that work exists in. A lot of musical acts would’ve disappeared without a trace had it not been for Hip-Hop beatmakers chopping and looping up sounds from previous decades. Eventually, some reissue labels got lucky enough to stumble upon completely unreleased gems . . . and this is the point of this story. What Amir mentioned to me in private blew my mind.

It’s a previously unreleased Charles Mingus Live recording with two new songs never heard before and a 15-minute interview with Roy Brooks the drummer. It’s from 1973 and recorded at the Strata Concert Gallery in Detroit. (Amir’s actual words from the text message he sent me on 9/3/18)

Needless to say, there weren’t enough emojis to express my excitement. With our hero making his spiritual transition in 1979, these 1973 recordings not only help us edit the history of his life as a performer/ composer, but they also help us connect the dots on Mingus as one seeking and supporting independent movements.

The unreleased performance took place at Strata’s Concert Gallery, and to be honest I didn’t even know that the place ever existed. While Strata, and labels like it, might’ve served as an independent outlet for musicians of the era, few labels had actual hubs to call their own. In fact, the link to Mingus’ spirit hits hard being that he ran a few small labels himself and might’ve thought about opening his own café or performance space at one time or another throughout his career.

The personnel includes Mingus (bass), Roy Brooks (drums/ musical saw), John Stubblefield (tenor sax), Joe Gardner (trumpet), and Don Pullen (piano). And while I’ve not heard the entire set (a preview of the evening’s events can be found here) with the inclusion of the legends Brooks, Stubblefield, and Pullen, I’m already convinced of satisfaction.

In recent years there have been many books published about Charles Mingus; some by feminist writers and music historians, and even by his widow, Sue Mingus. Yet, after reading his work Beneath The Underdog (1971) I realized that nothing spoke about the man more than his music. Whether on his own discs from the 1950s-1960s, his work being sampled, or the joy of hearing an unreleased concert, Mingus’ artistic and emotional output demands attention from the listener. He’s probably one of the earliest composers to force me to stop what I was doing and focus my energy on what had been laid down. I can’t wait to have that experience again when Mingus: Jazz in Detroit/ Strata Concert Gallery/ 46 Selden arrives at my doorstep.